|

|

|

|

|

![]()

Volume 6,

Issue 4, Summer 2003

On

Suffixes and Online Journals

Stephanie

J. Coopman

| Printer-friendly PDF version AbstractIn the American Communication Journal's inaugural issue, Michael Calvin McGee (1997) suggested that the journal embrace postmodernity rather than postmodernism. As the outgoing editor of ACJ, I'm not sure that we've quite reached Michael's dream. Yet in the 10 issues Norm Clark, the journal's associate editor, and I have published, I believe we've achieved at least a glimmer of Michael's vision. In this narrative, I describe my experiences with ACJ as contributor, reader, reviewer, and editor, tracing the revolution that began with ACJ 1.1. |

Communication

Studies San José State U San José, CA 95192-0112 sjcoopman@yahoo.com |

Let

me start from "a" beginning, as all good tales should. Ty

Adams, then an assistant professor at the U of Arkansas, Montecello,

gave a presentation at the 1996

Southern States Communication Association Convention on the Association's

website that he developed.

Not only was the website impressive, but SSCA beat the National

Communication Association, the International

Communication Association, and the regional communication associations

to the online punch. With that website, Ty catapulted SSCA into a future

that we now take for granted. I later realized that Ty's presentation

also dropped me into a wormhole with a blinding speed rarely observed

in academe.

Let

me start from "a" beginning, as all good tales should. Ty

Adams, then an assistant professor at the U of Arkansas, Montecello,

gave a presentation at the 1996

Southern States Communication Association Convention on the Association's

website that he developed.

Not only was the website impressive, but SSCA beat the National

Communication Association, the International

Communication Association, and the regional communication associations

to the online punch. With that website, Ty catapulted SSCA into a future

that we now take for granted. I later realized that Ty's presentation

also dropped me into a wormhole with a blinding speed rarely observed

in academe.

My quiet, low-tech academic life came to an end the day I introduced myself to Ty Adams at the 1996 SSCA convention. I told him how impressed I was with his work and his vision for the Association's website. I was hooked; I just didn't know how much. Seven years later, I teach online classes, edit an online journal, train my colleagues in online instructional resources, and design websites. What happened? That is the tale I will tell: A shift from, as McGee (1997) suggests, postmodernism to postmodernity, from reaction to action. At the time I met Ty, I could not have foreseen how he, and later Michael, would influence my conceptualization of creating and representing online scholarship. In this narrative I describe my experiences contributing to, reading, reviewing for, and editing the American Communication Journal.

Writing Online Scholarship

In September 1997 I received a frantic email from Ty Adams, then ACJ's editor, who with co-editor Jim Kuypers launched the journal. He asked that I write an editorial for the journal's first issue—and have it to him in a week. Okay, I could do that. I didn't know HTML, didn't really understand how a web browser worked, and thought that a 33.3 modem was fast. I started writing in my usual word processing program, but soon found it awkward trying to indicate where I wanted to include hyperlinks and graphics. So I switched to a web editor (that shall remain unnamed), learning how to use it as I wrote. I finished the editorial on time, learning how to FTP, embed a hyperlink, and download a graphic. As soon as the issue was released, I sent the URL to all my colleagues and friends. I also reformatted my computer's hard drive, as it crashed just after I emailed the files to Ty.

Thus

began my online publishing career. At the time, I didn't envision the

far-reaching consequences of my participation in ACJ's debut issue,

or the impact the journal would have on the discipline. In addition, until

I began my tenure as ACJ's editor, I didn't fully comprehend Michael

McGee's crucial role in steering the journal's course.

Thus

began my online publishing career. At the time, I didn't envision the

far-reaching consequences of my participation in ACJ's debut issue,

or the impact the journal would have on the discipline. In addition, until

I began my tenure as ACJ's editor, I didn't fully comprehend Michael

McGee's crucial role in steering the journal's course.

Since my first venture in online writing, I published a second editorial (Wood & Coopman, 1999), an invited article (Coopman, 2000) and three peer-reviewed essays (Coopman & Applegate, 2000; Coopman, Hart, Hougland, & Billings, 1998; Coopman & Meidlinger, 1998) in ACJ. I find writing for an online journal liberating in the sense of the resources available on the web, and constraining in that the audience extends far beyond the discipline and even academe. Thus, writing for an online journal is qualitatively different in terms of the essay's embeddedness in the larger electronic discourse, the technology that can be incorporated into the "text," and the wide-ranging nature of potential readers. Writing for an online journal forces the author to consider the placement of her or his ideas within the digital ocean of knowledge.

I've also published in traditional paper venues and found the experience less than satisfying. Paper journals constrain authors in space and technological resources, but liberate authors in that the audience is narrow and homogeneous. Thus, I can use all the jargon I'd like, but I can't include a hyperlink to a relevant website that the reader might find useful or drop in an image, movie, audio file, or other visual that would replace a three-paragraph description. Traditional paper journal articles suggest an isolation from anything outside those bound pages. Yes, we cite others' work and list our references at the end of our papers. Readers can then track down those citations—but do they? When? The immediacy vanishes, and often with it, the reason for looking up that reference.

Online writing challenges the linearity of writing for paper. Just as online readers click and jump within a page, between pages, and to another website, online authors go beyond the building-block approach to writing we were taught in school. The Digital Age has brought with it a greater emphasis on narrative and non-traditional writing styles, even in the dusty halls of academe. Thus, we may write online and include multiple windows, video clips and audio files that may take readers "out of" the main text for a moment or an hour. Essays may be structured so readers might access any section from any other section with a mouse click.

Publishing an article in an online journal also provides a venue for interaction between author and reader, as the author is only one click and an email message away. As the technology becomes less expensive and more accessible, we'll see greater use of this interactivity and a blurring of author/reader roles, as we've begun to see a blurring between researcher/study participants (Coopman, 2001).

Reading Online Scholarship

Because I contributed an editorial to ACJ's debut issue, I wrote for the journal before I ever read it. Reading an online journal article can produce both frustration and excitement. Following links, sorting through multiple screens, and downloading audio/video files may lead to losing one's way in the article. In that respect, we may miss the author's main points as we follow all the divergent trails the author has included.

Alternative formats can hinder rather than assist the article's readability. In one ACJ essay, the authors present their article in 19 separate documents, not including asides or additional comments. Readers can only go back and forth between the separate pages in a linear fashion (e.g., from page 3, readers can only view page 2 or 4). Thus, there is a sense of disconnectedness between the authors' various points and arguments. The essay appears formatted for style rather than enhancing the reader's experience. Online journal readers may encounter other questionable formatting decisions, such as distracting backgrounds, lack of contrast, too many images, animated gifs, and blinking text, present barriers that readers are unlikely to overcome.

Online authors may also believe that since theoretically they have unlimited space, they should provide readers with an abundance of information. Without a word limit to force thorough editing and concise writing, online scholarly essays may buckle under their own verbage. In addition, links, images, and other resources are not always chosen judiciously and have little relevance to the author's arguments and topic at hand. The reader becomes overwhelmed with information and will likely give up trying to understand the essay's point.

As I visit websites I didn't even know existed and listen to parts of a speech on which form the author's "data," I become more immersed and intrigued with the topic. Images that explain an author's point and appropriate graphics that would be prohibitively expensive in a print journal enhance reader comprehension and make the author's arguments more robust. Images, generally kept to an absolute minimum in print journals, may also impact the reader in ways that a verbal description cannot. For example, I had read about the television ads broadcast in the 2000 presidential campaign, but without cable and receiving only a single station with any kind of consistency, I didn't have sense of the discussion (and debate) related to the ads. Viewing the ads (stills and video clips) in Glenn W. Richardson, Jr.'s (2002) essay gave me a new understanding of the issues associated with the ads. And reading the lyrics of "New Rhetoric" (sung to the theme song for "Hee Haw") simply lacks the impact of listening to Robert N. Bostrom, Derek R. Lane and Nancy G. Harrington (2002) sing the tune they wrote. When authors engage journal visitors in this way, ACJ moves closer to postmodernity and farther away from postmodernism.

Viewing

an image or listening to an audio file on which the author's analysis

is based promotes the reader's own interpretation or analysis. Thus, I

may view the images and listen to the audio files Jon Radwan (2001)

included in his essay

on presentational symbols and rhetoric, concluding, "Jon's analysis is

right on target." Or I may think, "I have an alternative interpretation."

Similarly, Xin-An Lu (2001)

includes images he analyzed of the Dazhai

campaign posters used in China during the 1960s and 1970s to promote

team work and diligence in farming. In either case, I can email the author

with my comments by clicking on the email address link.

Viewing

an image or listening to an audio file on which the author's analysis

is based promotes the reader's own interpretation or analysis. Thus, I

may view the images and listen to the audio files Jon Radwan (2001)

included in his essay

on presentational symbols and rhetoric, concluding, "Jon's analysis is

right on target." Or I may think, "I have an alternative interpretation."

Similarly, Xin-An Lu (2001)

includes images he analyzed of the Dazhai

campaign posters used in China during the 1960s and 1970s to promote

team work and diligence in farming. In either case, I can email the author

with my comments by clicking on the email address link.

Probably the most powerful feature of online journals is site-specific search engines. I couldn't begin to estimate the number of hours I've spent searching in paper journals for an article I only vaguely remembered. Typically, I have a distinct impression of a cover ("I'm sure the article was in the Southern Communication Journal because I recall the blue and white colors"), only to locate the article hours (or days) later in an entirely different journal than I had remembered. In addition, the search function may locate articles relevant to my topic that I might have otherwise missed.

Reviewing Online Scholarship

My membership on the ACJ editorial board began in 1997. Although fairly new to this idea of an online academic journal, my enthusiasm for what an online journal represents and might do led me to readily agree to serve on the board. At the time, I thought reviewing online essays would be more efficient and take less time than a paper journal. Although a completely paperless review process does speed up editor-reviewer contact, evaluating an online submission requires a multidimensional approach to the process.

An

online journal isn't just a paper journal put into HTML or PDF (although

ACJ does include "printer-friendly" pdf files of most essays).

An online journal makes full use of the web, integrating sound, movement,

images, hypertext, and text. The potential audience may include anyone

with internet access. Thus, articles submitted to an online journal must

not only reflect good scholarship; they must demonstrate creativity and

accessibility in style, format, and presentation. In reviewing articles

submitted to ACJ, I evaluated how authors used internet resources

as well as the essay's traditional content. With online publications,

it is not enough to just make good arguments within the tiny world of

academe. Authors must identify ways in which their research fits in or

links to other places in cyberspace, as well as write in a clear, accessible

style.

An

online journal isn't just a paper journal put into HTML or PDF (although

ACJ does include "printer-friendly" pdf files of most essays).

An online journal makes full use of the web, integrating sound, movement,

images, hypertext, and text. The potential audience may include anyone

with internet access. Thus, articles submitted to an online journal must

not only reflect good scholarship; they must demonstrate creativity and

accessibility in style, format, and presentation. In reviewing articles

submitted to ACJ, I evaluated how authors used internet resources

as well as the essay's traditional content. With online publications,

it is not enough to just make good arguments within the tiny world of

academe. Authors must identify ways in which their research fits in or

links to other places in cyberspace, as well as write in a clear, accessible

style.

In addition to all the demands of reviewing submissions to paper journals, online journal reviewers examine hypertext links embedded in the essays, determine the usefulness of audio files and images, and evaluate the appropriateness of alternative formatting. Reviewers must place essays both within the stream of academic research and the stream of cyberspace. Authors may have difficulty making the transition from paper to online writing, so part of the reviewer's task lies in assisting authors with that transition. As a reviewer for ACJ, I provided authors with suggestions for incorporating online resources into their essays in meaningful ways. I sought to fulfill Michael McGee's (1997) vision of ACJ as "a whirl of activity on these screens, not just the bloodless publication of scholarship, but the embodied and enacted, contested and appreciated, performance of scholarship."

Editing Online Scholarship

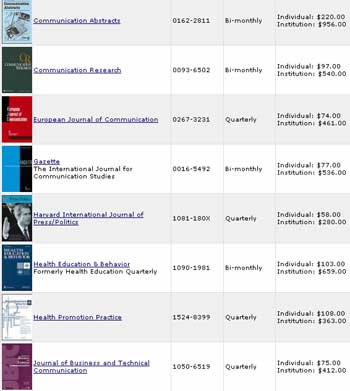

. . . a letter from the responsible administrator that institutional support, including release time, administrative support, and financial support (supplies, shipping, copying, etc.) will be provided (from a call for editors in Spectra).The two sample price lists below offer a useful reminder of a paper journal's costs. In communication, the individual rates for a journal subscription run about $10-20 per issue, with the library rates up to six times that amount. But consider the plight of scholars in material sciences! Those folks commonly pay thousands of dollars each year for their journals, and individuals pay the same price as institutions. At over $100 per issue, I doubt faculty are lending out their journals to students, or even to other faculty.

sample Sage journals in Communication who profits from scholars' free labor? |

sample Sage journals in Material Sciences spendy! |

Although Courtright (1999) argues that converting paper issues of journals into an electronic format is enormously expensive, completely online journals are inexpensive to produce. For example, the U of Arkansas, Fayetteville, provided the original server space for ACJ. Appalachian State U now hosts the ACJ domain name and so far provides us with plenty of server space. The American Communication Association pays $35 per year for the ACJ domain name, acjournal.org, and the occasional printing costs for flyers that we distribute at conventions. Books for review are handled much like paper journals, with the book review editors' institutions bearing the costs of shipping books to reviewers.

The main cost is time. ACJ is its own publisher in that the editors publish the webpages that constitute the journal. Associate editor Norm Clark handles most of the coding duties, with Stephen Klien preparing the book reviews for the ACJ website. So along with our authors and the editorial review board, the ACJ editors decide what will be published in the journal and what won't. Although the editors are still the journal's gatekeepers, we are not constrained by page limits and paper publishing costs. In his discussion of electronic journals, Benson (1998) argues that these journals "promise to lower the barriers to publication, which should give individual scholars more publication opportunities and produce for a society a richer base of scholarly resources." By lowering one publication barrier, cost, and by making the journal available to anyone with internet access, ACJ provides those within and outside academe knowledge that was previously trapped in paper texts, gathering dust on a library's shelf.

As Hugenberg (1999) points out, the cost of paper often constrains what can be published in a journal. In editing Communication Teacher, Hugenberg found that with the paper format: "Some good teaching ideas are not published due to their length. Even worse, these print restrictions might deter a prospective author from even submitting her or his ideas because it cannot be explained adequately in 1200 to 1500 word limit." Hugenberg argues that shifting CT to an electronic format (begun in fall 1999) will greatly benefit: (1) readers by producing timely, complete information; (2) authors by giving them opportunities to fully elaborate on their ideas; and (3) editors by providing flexibility not available in paper journals.

With the very low monetary costs of an online journal comes the possibility of true innovation in how we represent our research and other scholarly endeavors. Benson (1998) argues that "easy access to publication could . . . produce genuine intellectual benefits by providing outlets for innovative scholarship and by providing the assurance that highly specialized, ongoing programs of research will not lead to a dead end in a gatekeeping process that has turned its favor elsewhere." For example, Myria Allen guest edited ACJ 6.1 in which scholars discussed and presented their creative accomplishments about who they are and what they do as communication scholars—a meta-commentary on disciplinary identity. Authors will included their artistic presentations (e.g., songs such as, "Make Me a Dean" or "Apprehension") as well as essays introducing their creative works. Issue 6.3 on performance studies, with Marc Rich, David Olsen, and Julia Johnson as guest editors, includes two installations that, as Norm Clark notes, push "the boundaries of what we've done so far with this journal. As such, it probably will push the boundaries of your computer." Using Shockwave and Flash, the authors get at the performing part of representing scholarly McGee envisioned for ACJ.

Online journals, at least ACJ, remain independent from the constraints that typically influence paper journals. Yet, ACJ is dependent on its staff and university server host for its survival. Because the journal relies on a public institution of higher education for server space, we cannot accept advertisements of any kind. Some may see this as a negative aspect of the journal; others welcome the absence of advertising in a scholarly journal. Thus far, neither the U of Arkansas nor Appalachian State U has tried to limit, influence, or alter ACJ's content in any way.

With our independence, however, also comes greater responsibility on the staff to promote the journal. Current and previous editors have developed their own strategies for advertising the journal, including specialized business cards, pamphlets, and listserv postings. We make announcements at professional business meetings, attend panels and solicit contributions, and encourage our colleagues to submit their work to the journal. Unlike publishers such as Sage and Lawrence Erlbaum, we don't have the resources to launch an advertising campaign for the journal. Unlike the National Communication Association, the International Communication Association, or even the regional associations, we don't have a large membership base to whom we can pitch the journal.

In some disciplines online journals are championed for their cutting-edge research and innovative formats. For example, the Public Library of Science's first journal, PLoS Biology, goes online in October 2003, with PLoS Medicine scheduled for its first release in 2004. PLoS rightly argues,"Immediate unrestricted access to scientific ideas, methods, results, and conclusions will speed the progress of science and medicine, and will more directly bring the benefits of research to the public." PLoS, like ACJ, stresses its commitment to open access: "Unfettered access to research literature will allow scientists, physicians, educators, students, and the general public to find and read the latest scientific and medical discoveries." As PLoS reminds us, we should disseminate our research widely so it reaches all those who might benefit, rather than just to an isolated few.

Yet, in communication, online journals may encounter skepticism. I'd become fairly complacent about ACJ's "respectability" until a recent incident my spouse experienced. In a paper he wrote for his core graduate class on public scholarship in the Department of Communication at the U of Washington, he referred to ACJ as an example of accessible scholarship. Unfortunately, both instructors of this team-taught class questioned ACJ's legitimacy, suggesting that the journal lacked disciplinary "esteem." The instructors downplayed ACJ's impact on the field, citing inclusion of the journal in my spouse's paper as a "weakness."

Still, in spite of the skeptics, the word is out about ACJ. The journal is registered with the U.S. Library of Congress. Communication Abstracts lists ACJ. Two ACJ articles were included in a recent Sage publication, Intercultural Communication: A Global Reader, edited by Fred E. Jandt (2003). Top people in the field, such as Jim Applegate, Moya Ball, Edwin Black, David Boje, Brant Burleson, Dana Cloud, Carolyn Ellis, Robert Ivie, Andy King, David Ling, Michael Calvin McGee, Martha Solomon, Jill Taft-Kaufman, and Nick Trujillo, have published in ACJ. Our editorial board includes Steve Duck, Joy Hart, Pamela J. Kalbfleisch, Gary Kreps, Nancy Grant Harrington, Raymie McKerrow, Roxanne Parrott, Richard Ranta, and Irving J. Rein. ACJ averages thousands of unique visitors each month. There is no question that people seeking scholarly knowledge about the communication discipline have found ACJ.

Conclusions

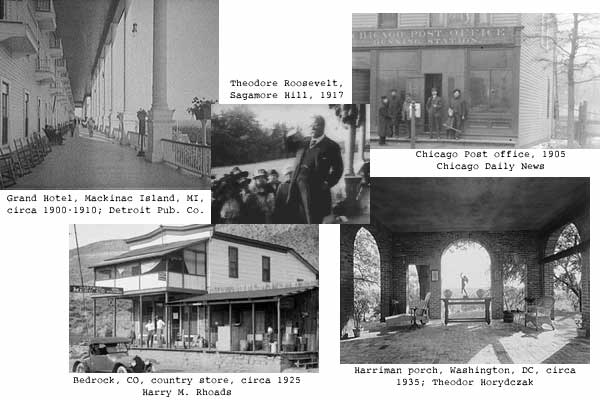

Porches enjoy an important place in U.S. history as sites for people to discuss the issues of the day, visit with friends and family, and watch the community's daily comings and goings. In 1917, Theodore Roosevelt spoke on woman suffrage from the front porch of his home, Sagamore Hill, in New York state. The front porches of old post offices were a place to swap stories with neighbors. Country stores featured a wide front porch for selling goods, talking with other customers, and resting in the shade. Theodor Horydczak, a Washington, DC, professional photographer, featured front porches in several of his works. The Grand Hotel on Mackinac Island, Michigan, has the world's longest front porch—660 feet.

Porches in U.S. History from the Library of Congress American Memory Collection |

At the beginning of the 21st century, porches continue in their importance for building community, meeting others, and exchanging ideas. In the essay I wrote for ACJ's debut issue, I concluded:

People will most definitely come to our virtual front porch; some already have. Our goal should be to welcome divergent voices from many places to enter the conversation. ACJ has the potential to mark a shift in how we report scholarship and who gets included in the dialogue. In these respects, the stoop metaphor incorporates both stupa and stump: ACJ's virtual front porch can provide a sacred space (stupa) for activist and accessible research (stump). If we gather enough voices on our virtual front porch, ACJ will remind us of what was once good scholarship and demonstrate that it can be good again (Coopman, 1997).Although some have predicted the demise of online journals (e.g., Courtright, 1999), ACJ, the Electronic Journal of Communication, Online Journalism Review, the Electronic Journal of Radical Organisation Theory, and other e-journals suggest that they're here to stay. In addition, current ventures by more traditional organizations, such as the National Communication Association, into electronic-only journals indicate that e-journals are fact rather than fad.

A Scout Report review suggests that ACJ is achieving its commitment to accessible, meaningful scholarship presented in web-sophisticated formats. The editor and reviewer David Charbonneau (2001), states: "The journal is dedicated to discussing communication theory in ways that reach beyond the often arcane world of academia. To this end, many of the articles are written in more accessible prose (relatively speaking), and many feature hypertext with links to articles, media, and Websites in the popular arena, e.g., the issue on Clinton includes a QuickTime video of the former President vehemently denying he had 'sexual relations with that woman.'"

In an issue of the ICA Newsletter, Lievrouw (2001)argues that the electronic publishing business has not met projected expectations. E-books haven't really caught on; broadband hasn't replaced the modem in most homes; and hardware problems plague the storage of large files (particularly video). That may be true for e-publishing business, but for a journal such as ACJ, minimal cost has produced maximum benefits. ACJ always has been and always will be free to readers. Thus, ACJ not only embeds scholarship within the web, it also reflects the original intention of the internet's development: sharing information.

The use of "free" labor for publishers' profits, cost, isolation, tedious (if any) search tools, inaccessibility, bereft of graphics and images, lacking in multimedia, distant—these qualities do not bode well for the paper journal. Although paper journals may never completely go away, online journals will certainly gain in popularity, if for no other reason than their practicality. Sooner rather than later we'll look back fondly on the days of paper journals, and say a word of thanks for the online journal as we browse through articles on our hand-held personal digital assistants.

We may not have achieved McGee's (1997) vision of a cybering journal that's "a site for creative theory construction, a place where the big questions are posed and discussed." But I think ACJ embodies the spirit of his call to change the suffix from -ism to -ity, as the journal offers "the life of the mind . . . a more public, faster-paced visage."

Back

to Top

Home | Current

Issue | Archives | Editorial

Information | Search | Interact