|

|

|

|

![]()

Volume 6,

Issue 2, Winter 2003

Breaking

Through the Glass Ceiling Without Breaking a Nail: Women Executives in

Fortune Magazine's "Power 50" List

Sherianne

Shuler

|

Printer-friendly PDF version AbstractHewlett-Packard CEO, Carly Fiorina, recently declared that "there is not a glass ceiling" (Ackerman, 1999, p. 44) in today's organizations. Seemingly supporting this declaration, Fortune magazine recently started publishing "The Fifty Most Powerful Women in American Business," with Fiorina at the top of the list each year. While the increasing number of women executives perhaps demonstrates progress, the magazine coverage perpetuates familiar stereotypes of women in organizations. By positing that popular business magazines are part of the broader discourse in which organizations are situated, this paper examines Fortune's "Power 50" lists, arguing that they help to construct the glass ceiling. |

Assistant

Professor Dept. of Communication Studies University of Alabama Box 870172 Tuscaloosa, AL 35487 sherishu@bama.ua.edu |

In 1998, Fortune Magazine published its first issue of "The Fifty Most Powerful Women in American Business" ("Power 50"). When I noticed this cover story on the magazine rack, my first inclination was to say "Hooray! Finally they are paying attention to women in business!" And at face value, the existence of this list (which debuted in 1998 and has been produced annually since) looks like an example of liberal feminist triumph in the public sphere. Certainly, there have been gains for women (particularly white women) in the past few decades. Nevertheless, according to data collected by Catalyst, progress remains slow. The January 2002 issue of Perspective notes that while there were no women CEOs of Fortune 500 companies in 1962, by 2002 there were 6. And while 15.7 percent of all corporate officer positions are now held by women, when the numbers are broken down by race it becomes clear that recent gains have primarily advantaged white women, as women of color hold only 1.6 percent of corporate officer positions (Catalyst press release).

As I paged through Fortune"s first "Power 50" issue, my excitement about women's progress in the business world faded as I grew increasingly irate at the photographs of the women that were interspersed throughout the article. Although Fortune is a business magazine, the photographs looked as if they belonged in Glamour or Vogue. Looking beyond the visual representation of businesswomen to the language that is used to describe them, it seems clear that Fortune's treatment of women in business serves to reentrench patriarchal views of organization. While purporting to be breaking new ground, Fortune's depiction of women actually seems to just move the male gaze to a new arena.

Organizations and their members are embedded in ever widening communities, and are shaped in and through broader cultural discourses of power, gender, and the meanings of work and success. One entry into these broader cultural discourses is through popular business magazines. While many communication scholars have focused on popular media, this scholarship has not permeated the study of Organizational Communication (Management Communication Quarterly's 2001 forum edited by May and Zorn on popular management writing is a notable recent exception). If organizations are social constructions with boundaries that transcend the outdated "container" metaphor, then the popular media that business people access certainly must be recognized as contributing to organizational discourse. This paper argues that the popular business press is a powerful participant in gendered organizational practices. After a discussion of the theoretical underpinnings of the paper, as well as a brief review of research in feminist organizational communication and gendered media, the focus moves to Fortune magazine and its "Power 50" list. Finally, I offer a brief case study of the press coverage of Carly Fiorina, Fortune's number one pick for three years running.

Theoretical Commitments: Organization, Feminism, and Media

Giddens (1979) structuration theory holds that social structure is continuously produced and reproduced through the agentic interaction of individuals. Building on Giddens' work, Boden (1994) argues that, not only do we talk about organization, or in organization, we talk organization into being. Although Giddens' work has been applied in organizational communication in a variety of ways, it is the metatheoretical level that is most relevant for this paper because of the duality of agency and structure the theory posits. This perspective holds that organizational structures are not concrete realities, but are dynamic, discursive, and always created and recreated through the agentic action of individuals, who are themselves constrained by the structures they help to produce. While we might tend to reproduce structures similarly over and over, we could choose to do otherwise. It is important to note that in his discussion of agency, Giddens (1989) argues that human action always produces both intentional and unintended consequences. Thus, structures produced and reproduced are not always intended as such by the individuals who discursively contribute to their creation. If, as Giddens (1989) suggests, communication is central to social structure, then communication is also central to the process of struggle and potential transformation.

Organizational communication scholars often get stuck talking about organizations as "containers," as if they are bifurcated from their environments (Smith, 1993; Smith & Turner, 1995). While this rhetorical construction can be difficult to escape, it traps us into thinking too narrowly about the process of organizing. The container metaphor causes us not to "see" (or, rather, "hear") the ways in which organizations are situated in larger communities of discourse. This is one tendency this paper attempts to resist. Another is that when we talk of structures (of oppression or any other kind), we often speak as if these structures somehow exist apart from individuals. But oppressive discourses of patriarchy, white supremacy, heterosexism, and capitalism are no more "prior" than any other kind of socially created entity. Buzzanell (1995) calls us to not simply take the glass ceiling as a given and then study its effects, but to study its processes--those language and interaction patterns which help to perpetuate traditional gender ideologies and hold up the glass ceiling. I argue that one pattern of interaction that helps to prop up the glass ceiling is the rhetorical construction of the images of business people in the popular business press. Again, it is important to acknowledge that this can happen with or without malicious intent on the part of the producers of these images, and can be an unintended consequence of their actions. The structures that are created and maintained through our actions, ostensibly, can also be resisted and altered through discursive action.

Feminist Organizational PerspectivesWithin the field of organizational communication, scholars have been quite successful at laying out the theoretical basis for feminist scholarship (e.g. Bullis, 1993a; Buzzanell, 1994; Marshall, 1992; Martin, 1992; Mumby, 1993), and in demonstrating the perpetuation of oppressive organizational structures such as sexual harassment (e.g. Clair, 1993), sex discrimination (e.g. Boggs, 1998), and the glass ceiling (Buzzanell, 1995). Another successful area of feminist organizational inquiry has been to "re-vision" organizational processes such as socialization (Allen, 1996; Bullis, 1993b), emotion management (e.g. Mumby & Putnam, 1992; Shuler & Sypher, 2000; Tracy, 2000), and negotiation (Kolb & Putnam, 1997) through a feminist lens. Buzzanell's (2000b) notable recent book, Rethinking Organizational & Managerial Communication from Feminist Perspectives, is demonstrative of the emergence and coalescence of a feminist paradigm within organizational communication.

One chapter that appears in Buzzanell's (2000) collection is particularly germane to the purpose of this paper. Trethewey (2000) employs a feminist analysis of the disciplining of the body in organizational life. In her interviews with women from a variety of occupations and organizations, she demonstrates the ways in which many female bodies are not seen as "professional." Using the concept of Foucault's (1979) panopticon, she argues that workers, who are situated within a broader culture that glorifies only certain body types and styles, discipline themselves and one another to live up to "professional" body standards of fitness, dress, and nonverbal action. Further, since "professional" bodies have traditionally been defined as masculine bodies, women find themselves navigating within a discourse that defines their bodies as inherently "unprofessional."

The paradox is that while feminine bodies are supposed to be controlled, asexual, and hidden, if women go too far in transgressing feminine appearance norms, they also face negative consequences. Employing a poststructuralist feminist perspective in her analysis, Trethewey (2000) successfully blurs the boundaries between organizational discourses and broader societal discourses. Further discussion of the broader cultural discourses and some of the specific places where we can see the disciplining of feminine bodies is a logical extension to Tretheway's work. This paper explores one cultural contributor to the construction of the female professional body, portrayals of women in the popular business press.

By examining Fortune's "Power 50" issues, I hope to offer an example of scholarship that attempts to avoid the bifurcation of the organization and its environment. By choosing to look at a business magazine as a site of organizational discourse, I acknowledge that the view of organization is limited. Nonprofit organizations of all types, including religious, educational, and governmental organizations, are not the focus of business magazines. In addition, the coverage in such magazines tends to mainly focus on large corporations, rather than small businesses. Choosing this magazine as a focus necessarily privileges "corporatized" views of organization, rather than alternative organizational arrangements. I do not claim that an examination of Fortune will yield results that are generalizable to all organizational discourses, but I do claim that Fortune both creates and reflects at least some of the discourses of U.S. corporate life. While U.S. corporate life is just one slice of organizational reality, it is inarguably the most privileged. This is precisely why it is appropriate to examine its possible contributions to the sociocultural milieu that surrounds, creates, and constrains organizations.

Gendered Media and Popular Business MagazinesWhile an exhaustive review of the role of the media in shaping our notions of gender is beyond the scope of this paper, a brief discussion of some of the main issues is needed here. Hall (1989) claims that all media are ideological, which means simply that all media socially construct meaning. One important role of the critic, then, it to examine these ideologies and how they are constructed and operate. Media ethicist Elliott (1996) argues that the mass media has a special moral responsibility to avoid publishing "images that injure" (p. 3), and injury should be defined as "perceived harm" (p. 5). Even though Elliott (1996) grants that producers of media perhaps do not intentionally and maliciously cause harm, this does not excuse their special responsibility that their power to influence grants them.

The relationship between media and their audiences is a complex and dynamic one. While there are a number of ways to think about this relationship, the work of Stuart Hall has been particularly influential in this regard. Hall (1980) argues that producers and audiences can read texts in three main different ways. The dominant, or hegemonic, reading is when reader who decodes a text shares and fully accepts the producers' preferred meanings. A negotiated reading occurs when the reader partially accepts the producers' meanings, but also resists and modifies some meanings based on the reader's own positionality. In an oppositional, or counter-hegemonic reading, the reader places herself or himself opposite the producer's preferred meaning. The oppositional reader may understand the hegemonic reading, but rejects it by using an alternative frame of reference by which to interpret the text.

In addition to examining how texts are read, many critics focus on how media images are presented. For example, many scholars have commented on the underrepresentation of women in media. Basow (1992) for example, notes that prime time television programming features three times as many white men as white women. And when women are portrayed on television, the picture is certainly not representative of all women, and tends to reinforce the dominant white, middle-class, heterosexual perspective. Connecting this reality to the commercial nature of television, Dow (1995) points out that women on television are usually attractive, wear makeup, and wear expensive clothing. While television programming does have the power to provoke social change, and audiences sometimes do resist dominant hegemonic messages, the commercial nature of television typically does not encourage resistance to the status quo--at least not enough to encourage audience members to systematically reject the products sold by advertisers to women, those which prop up the beauty culture.

Of course, fictional television programming is not the only site of the creation of gendered identities in media. Similar observations have been made of such artifacts as advertising (e.g. Cortese, 1999; Goffman, 1979), the beauty culture (e.g. Schwichtenberg, 1989), and news (e.g. Sanders & Rock, 1988; Buzzanell, 2001). And, of course, there are magazines (e.g. Peirce, 1990; Tate, 1999). As Wood (1999) points out, "magazines abound, and each one is full of stories that represent men and women and their relationships, thereby suggesting what is 'normal'" (p. 299). Steiner (1995) points out that while women's magazines may provide women pleasure and escape, they rarely treat women seriously enough to provide content that goes beyond the encouragement of consumerism. Watkins (1996) notes a paucity of images of professionally achieving women outside of popular business magazines, with magazines targeted toward women or girls having few or no images of such women.

Even in business magazines, however, McShane (1995) found that women are significantly underrepresented, with women being less than 7% of senior management sources cited. Clearly, the creators of business magazines do not view or portray women as valuable sources of information. Although McShane (1995) acknowledges that business magazines exist within a larger society that devalues women, he concludes that business magazines do not simply reflect, but help to shape unequal power structures in business. As such, he argues, scholars should pay more attention to them.

One notable recent exception to the lack of critical scholarly attention to popular business magazines is Nadesan's (2001) examination of Fortune's promotion of globalization. She argues that what is left unsaid in the pages of Fortune is that the globalization of new technology is a form of colonialism that has resulted in increasing economic inequities. As perhaps would be expected by the title of the magazine, the coverage of global issues in Fortune uncritically and unquestionably accepts (and indeed promotes) the assumptions and values of capitalism, which helps shape contemporary managerial discourse. Given this uncritical and conservative coverage of the "new economy," one might expect to encounter a similarly uncritical discourse of gender and race.

Fortune and the Social Construction of "Businesswoman"

Among popular business magazines, Fortune ranks second only to Business Week in circulation, with 901,000 subscribers (http://www.MediaStart.com/). Fortune is known for its lists, most notably the lists which rank companies, with the "Fortune 500" being the most well known. They also annually publish such rankings as "America's Most Admired Companies," "The 100 Best Companies to Work For," "Best Companies for Minorities," and "The Fortune e-50." Lists that rank individuals include "All-Star Analysts," "America's 40 Richest Under 40," and the recent addition of "Most Powerful Black Executives" all of which list mostly men, but gender is not a criteria for making the lists. There is no male equivalent to "The Fifty Most Powerful Women in American Business," which Fortune has published since 1998.

The inaugural issue of the "Power 50" was not created without controversy. According to the "Editor's Desk" column written by Managing Editor, John Huey, "The moment I heard some of our editors planning to rank America's most powerful businesswomen, I knew life was about to get more difficult for me" (1998, p. 26). The editor goes on to describe the basic conflict that this feminist critic struggled with as I paged through the issue for the first time, "We are damned if we do and damned if we don't. Some of our smarter women staffers--and we have more than a few who wield huge influence at the magazine--argue that any project singling out women in this way 'ghettoizes' them, that we should cover women just like men, writing about them only when they are newsworthy. If we hew strictly to that approach, of course, other factions will say we ignore women" (Huey, 1998, p. 26). Of course, if framed this way, coverage of women creates a double-bind that is nearly impossible to escape. What goes unquestioned in this equation is the construction of "newsworthy," particularly for a managerial audience. Are "ghettoization" or "no coverage" really the only options from which the editors of business magazines can choose?

In feminist scholars' attempts to point out the sources of oppression, we often speak of "the media" as if it is a faceless and powerful entity that exists without the participation of individuals and organizations making choices. In the managing editors' candid (if somewhat dismissive and patronizing) discussion of the office politics surrounding this issue, the reader gets a glimpse of the way that "news" gets created--by people making arguments, just like the work of any other organization.

To support his construction of himself and his magazine as "good guys," Huey asserts their honorable intentions; "we at Fortune have dedicated ourselves to provocative coverage of women in the corporate world and many of the thorny issues they confront both in the office and at home. Remember last year's cover story, 'Is Your Family Wrecking Your Career?'" (1998, p. 26). That the current popular work/family discourse seems to focus only on the choices women make and the consequences of those choices for women is never problematized. Men, apparently, never face work/family issues, at least not in Fortune.

Analysis of Gendered ImagesThe editor of Fortune claims that the magazine is dedicated to "provocative coverage of women in the corporate world" (Huey, 1998, p. 26). Without a complete content analysis of the magazine, which is beyond the scope of this paper, his overall claim can neither be supported nor challenged here. Rather, as a feminist scholar of organizational communication, I offer what Hall (1980) would call an oppositional reading of Fortune's "Power 50" list. In doing so, I recognize that many people, perhaps the majority of Fortune's typical readers, would decode these texts differently, either employing a preferred or negotiated stance. I do not claim that my interpretation is necessarily more "true" in a positivistic sense, but I do hope that my arguments and examples demonstrate a powerful counter-hegemonic interpretation of the text.

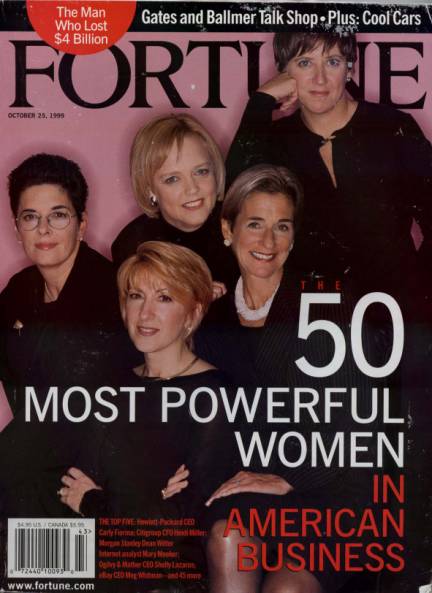

Analysis of the first three annual "Power 50" lists and the accompanying articles demonstrates some very troubling patterns. First, I examined the pictures of women in the main "Power 50" story in the first three issues, and attempted to categorize them into emergent themes. This examination did not include pictures in the surrounding stories, nor did it include advertising. This analysis yielded 70 total pictures falling into four thematic categories. The majority of the pictures (50 total) fell into the "traditional" category, meaning that they seem similar to the way that men are generally posed and are what a reader would expect to find in a business magazine, such as with this photo of Chase Manhattan's CFO, Dina Dublon from the 1999 issue.

This "traditional" category includes many very small head and shoulders shots and a few action shots on the actual fold out "list" page, which includes many small pictures and inflates this category quite a bit.

So, I grant that the majority of the pictures used in these "Power 50" issues do not seem out of the ordinary for the genre. However, more germane to this analysis are the other 20 photos, in which businesswomen are portrayed in keeping with gendered stereotypes. In general, these 20 stereotypical visual images are larger and receive more prominent placement in the articles. As such, they seem to overwhelm the other more traditional images and set the tone for the piece. The three stereotypical categories that emerged from the analysis are the "Homemaker," "Not an Iron Maiden!", and the "Cosmo CEO." These three visual categories were then used to guide the analysis of the written text, and written examples that fall into each stereotypical theme are interspersed throughout the discussion of the main categories. After each of these gendered stereotypes is discussed, the focus turns to the portrayal of race. The intersection of race, gender, and sexuality in Fortune's "Power 50" serves to reify the white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchal1 (hooks, 1995) status quo.

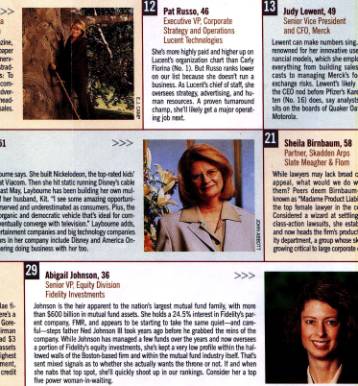

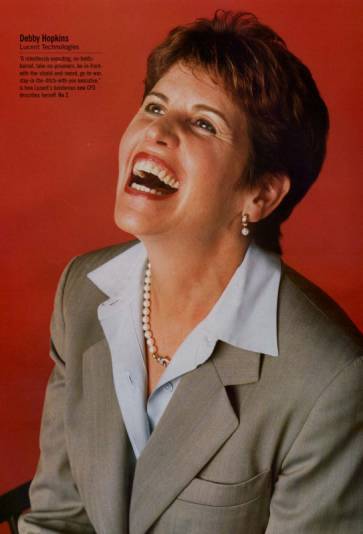

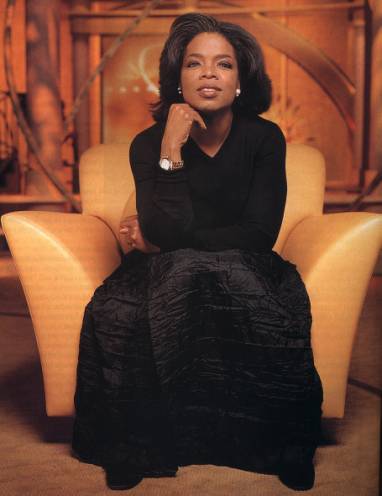

"Homemaker" The cover of the first "Power 50" list is striking because of how much it does not resemble Fortune's typical covers. Carly Fiorina2, then an executive at Lucent Technologies, is pictured wearing a sweater and sitting comfortably on a homey looking, pink, overstuffed chair. She is leaning forward, resting the side of her face on her hand, and the camera shoots her from above. Goffman (1979) argues that shooting a subject from above is a classic way to denote subordination, as is canting, or leaning the body or head to one side.

The cover looks very much like something one might expect from Ladies Home Journal or Good Housekeeping. It is an especially interesting choice, given that the second page of the article features a more traditional head and shoulders shot of Fiorina in a suit. Why did the editors choose the "homey" shot, especially given the fact that this woman probably spends many more hours in her "suit" role than in her "relaxing at home" role? In fact, despite being situated within a text that discusses at length these women's long hours and their sacrifices of family time, the "woman at home" image is still a popular one for portraying the "Power 50." Interspersed with small head and shoulders shots, the women are often shown posed in their living rooms, or with their children, or engaging in leisure activities. This example, also from the first issue, is of Citigroup's CFO, Heidi Miller.

The caption under the picture reads, illustratively, "A mom with two sons, she's about to become the CFO of Citigroup, the biggest financial company in the world" (Sellers, 1998, p. 78).

In addition to the "homey" and relaxed photographs of women, the text of all three issues spends time discussing the personal relationships of the women, especially how supportive their husbands are. It is emphasized that several of the "Power 50" have stay-at-home spouses, who are referred to as their wives' "secret weapons." Interestingly, while their husbands' stories of sacrifice are told in this article about their wives' career success, neither male executives who depend on stay-at-home wives, nor men's inability to "have it all" ever rates its own article. The second "Power 50" issue notes, in bold print, "Combining kids and a career is still hard. Meg Whitman says half her friends from Princeton and Harvard B-School have quit work to be full-time wives and mothers" (Sellers, 1999, p. 122). Indeed, the first issue also includes articles following the women of the Harvard MBA classes of 1973 and 1983, with several women noting the difficulty or impossibility of women "having it all" and featuring some who have given up their careers. Unlike their male counterparts, businesswomen are still portrayed as having to (or getting to) make choices between career and family.

In defining family, heterosexuality seems to be assumed, with specific references only to male relational partners included throughout the articles. Only in one instance is a woman said to have a "partner" whose gender is not named, although their ski slope wedding is mentioned. If any of the 150 women chosen in the three years of the "Power 50" are lesbians, this fact is not highlighted. Given the prominence of heterosexism in business and society, and the still very crowded corporate closet (Woods & Lucas, 1993), it is not surprising that homosexual women would choose to be quiet about their sexuality. Unfortunately, this silence also allows the norm of compulsory heterosexuality to shape the way we define "professional" bodies.

The second issue of the "Power 50" includes an article about the special mother-daughter relationship, and includes interviews with several of the mothers of top businesswomen. While it is somewhat refreshing to read about the importance of mothering, especially in a business magazine, it also furthers the notion of women as defined by their relationships. If this were to become a regular feature of Fortune's business coverage, and writers regularly talked to the mothers of powerful men, it could serve a transformative function. But as long as it is only women who have mothers, the construction of woman as "child" and as connected to relationships remains unaltered.

Other ways mothering is highlighted in all of the issues are through repeated references to the children of the "Power 50," and to the difficulties of balancing work and family. Several of the women are said to be putting off having children, or are reported to have made career sacrifices because of their children. Still more descriptions of the women include the ages and sexes of their children. Again, while a discussion of work/family issues in a business magazine may be refreshing, the fact that it continues to be presented only as a "women's issue" perpetuates the construction of businesswomen as mothers. Wood (1999) notes that working women often have to contend with their images as "mothers" (at home and at the office) and as "children" or "pets" (Kanter, 1977) who need to be protected. This category of the "homemaker" woman seems to capture aspects of both. While these are businesswomen who probably do not need to be protected, per se, the feature about their mothers does highlight their childhoods and portray them as more connected to family than their male counterparts. This traditional homemaker image may help buffer the criticisms that come from the "Not an Iron Maiden!" image, which is discussed next.

"Not an iron maiden!" Kanter (1977) notes that one stereotype that working women commonly contend with is the "iron maiden," or the woman who acts too masculine. Serious businesswomen are caught in a double-bind. Since our standard for what it means to be "professional" is a masculine standard, women who try to adhere to it risk being disciplined for going against gender norms. As Buzzanell (2001) points out, "white women and women of color still need to be competent and assertive as well as caring and nice, a behavioral prescription that can be difficult to enact" (p. 528). The powerful women who are celebrated in Fortune are those who are able to successfully solve this double bind, and the discourse and images of the women presented help to further buffer the "iron maiden" stereotype for these women. Thus, the second category of images presented is one of struggle. I call it "Not an iron maiden!" because it seems to feature poses designed to make women look soft and text that denies power.

Interestingly, several of the women on the first "Power 50" list were uncertain about whether they wanted to be identified as "powerful." One woman said, "power is a very dangerous word" (Sellers, 1998, p. 80) and another claimed, "I don't feel powerful." Jill Barad, the (now former) CEO of Mattel, observed, "when you apply the word 'power' to a man, it means strong and bold--very positive attributes. When you use it to describe a woman, it suggests bitchy, insensitive, hard...I'd rather be on a list of most interesting women. Or successful women" (Sellers, 1998, p. 80). Barad's words turned out to be unfortunately prophetic. By the time the third "Power 50 " issue was published, Fortune reported that Barad had been fired from her position by Mattel's board, having been "undone by intemperate ambition" (Sellers, 2000, p. 148). The same third issue names another former "Power 50" women who had been dropped from the list after being "axed" by her board for the same reason.

In a discussion of CEO Carly Fiorina's efforts to overhaul Hewlett-Packard, the article reports, "some gripe that Hewlett-Packard has become 'The Carly Fiorina Company'" (Sellers, 2000, p. 132), which seemingly demonstrates the tightrope that female executives walk. So while the magazine seems to be celebrating powerful women, it also serves to uphold the "iron maiden" stereotype--complete with warnings of what can happen to women who fit that persona. Although overall, the articles seem to accept the status quo and avoid taking a critical approach to discourses of power, it doesn't take much to read the subtext: When women are seen as too powerful, hard, or masculine, they risk complaints at a minimum, and getting "axed" at maximum. Women who want to succeed will do what they can to avoid the iron maiden stereotype.

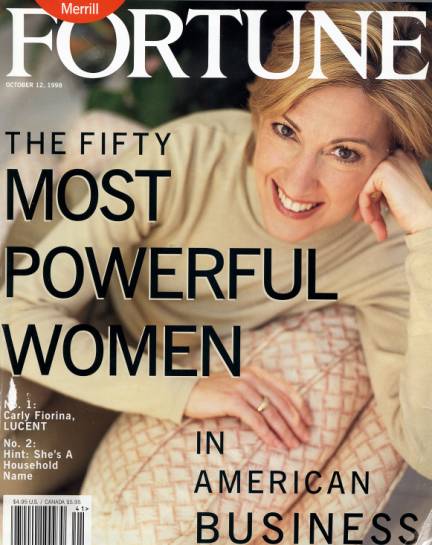

Many of the women featured in the articles claim to enjoy the power their jobs bring, but seem to work carefully to cultivate a powerful, yet soft, image. Debbie Hopkins, Lucent's CFO (who had been featured prominently in the second issue while she was the CFO of Boeing) was selected as the second most powerful woman in the third issue, and was described as having, "a backbone of steel and a deft touch" (Sellers, 2000, p. 131) and pictured laughing in a full page close up. Again, this read would hardly be surprising to Goffman (1979), who notes that women in photographs seem to smile more than men and often tend to be pictured in the state of childlike playfulness this picture connotes.

The pictures of the women in their workplaces are perhaps the most immediate and striking examples of the attempt to portray women as soft, yet powerful. Many women are pictured in soft colors, looking relaxed and friendly. Almost all are smiling. In addition to the head and shoulders or "homey" shots that have already been mentioned, one popular shot is a full body shot of a very femininely dressed woman posed amidst a traditionally masculine setting. The second issue shows (then) Boeing CFO, Debby Hopkins, in a hot pink suit and yellow flowing scarf posed in front of the engine of an airplane.

Similarly, Saturn President, Cynthia Trudell is shown wearing a pastel pink suit, in front of some jacked up cars.

Although people who really spend time working around airplanes and cars probably do not wear expensive pink suits, the visual contrast of masculine-feminine seems to say, "I can do a man's job, but still look like a woman." The juxtaposition of women against large machinery also makes the women appear to be small in stature, which is perhaps another way of warding off the "iron maiden" stereotype. Again, using Goffman's (1979) observations, since smaller relative size is a classic way to show low status, one might be left to read in both of these pictures that the women have less power than the machinery in their companies. Finally, one woman in the third issue is portrayed as using "woman's power--which, of course, has been confounding men for eons" (Sellers, 2000, p. 131). While her power is acknowledged, the characterization of her use of "women's power" seems to summon a more traditional, sexualized, and somewhat mysterious source of power for women. This sexualized portrayal of powerful women is explored further in the next section.

"Cosmo CEO" The focus on women's appearance also spills over into another of Kanter's (1977) stereotypes for working women, that of the seductress. In recent years, this image seems to be increasing, rather than decreasing, as Buzzanell (2001) notes in her critique of a Wall Street Journal article that celebrates an increase in sexualized attire for women, sexual banter, and flirting as a positive consequence of a more gender balanced workplace. In keeping with the sexualized portrayal of women in media, most of the women pictured in Fortune are slender and attractive, and all seem to be wearing makeup and are fashionably dressed. While the cover of the first issue resembles Ladies Home Journal, the cover of the second issue resembles Glamour or other fashion magazines. The editor's column of this issue is entitled, "Women in Black," and describes how the creators of the article "cajoled, called (and called and called), and finally convinced the top five, who all showed up in New York City at 4pm on Sept. 10" for the photo shoot (Fraker, 1999, 28).

The five women, all wearing black, are posed together in a style much more reminiscent of a Gap advertisement than a business magazine. This cover portrays the "Power 5" as savvy and stylish, leaning on and touching one another in a way that seems more appropriate for old friends than for business competitors. In Goffman's (1979) terms, their "women in black" costumes and their childlike posing makes the whole shot look like more of "a lark" (p. 51) than a typical business magazine cover and locates the women as "less seriously present" (p. 51) than their male colleagues.

Indeed, all three issues feature pictures that seem curiously out of place for a business magazine. The first issue shows the second most powerful woman, Oprah Winfrey, leaning forward seductively while wearing an evening gown.

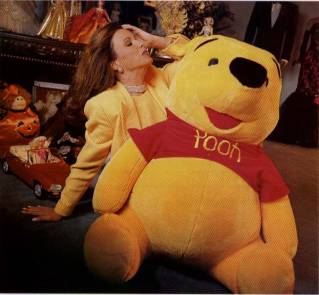

Perhaps this is not all that surprising, given that her business is entertainment, but her prominent "glamour shot" presence among more conventional businesswomen seems to lend credence to the stereotype that a woman's power is through her glamour and physical attractiveness. Also in the first issue, Mattel CEO, Jill Barad, shot from above, is pictured with her eyes closed, leaning back, and running her fingers through her hair.

Curiously, this highly sexualized photograph also includes a large Pooh bear, providing a disturbing juxtaposition of the sex object and child stereotypes. Before she was "undone" by her "intemperate ambition," Barad was apparently "undone" by Winnie the Pooh. The third issue features a picture of Avon CEO, Andrea Jung with a seductive expression, short skirt, and cleavage.

Several other photographs in all three issues prominently feature the legs of women wearing short skirts, or sultry and provocative facial expressions.

It should be noted that not all the photographs in Fortune's articles are taken by the magazine staff, some are most likely provided by individual businesswomen or their publicists. In addition, it may well be that some (or perhaps even most) of the women approve of the way in which their bodies were displayed in the articles. Even if both of these contingencies are granted, the larger point of this oppositional reading is not derailed. Just because individual women do not feel objectified by sexualized images of themselves does not preclude the images from doing rhetorical damage through the construction or promotion of stereotypical group identities. While I argue that Fortune magazine, and the media in general, do a great deal to shape our constructions of the successful and powerful businesswoman, they certainly could not do this without the participation of the women and the rest of us who contribute to the various discourses that both constrain and enable organization. If "professional" bodies are fit and attractive bodies, as Tretheway (2000) argues, then it is because they are discursively created as such. And as we know, for oppressive discourses to maintain their power, they must have many conversational advocates who consent (even unwittingly) to hegemony.

White PowerIn addition to the discourses of patriarchy and heterosexism, the discourse of white supremacy shouts loudly from the pages of Fortune. In the first of the three issues, there are three African-American women who appear on the list. Oprah Winfrey appears on the list and in pictures in the articles all three years. Of the two other African-American women who are also pictured in the first year, one is not included at all the next two years, and one is included but not pictured in the second year. As far as can be deduced by the text and photographs, no other African-American women have been added to the list since the first year. All three issues prominently include one Asian-American woman, Andrea Jung, who is currently the President of Avon. And has already been demonstrated through photographs, both of these women of color are sexualized. The third year also includes one traditionally pictured Indian born woman, Indira Nooyi, who is the CFO of PepsiCo.

So, it appears that of 150 women chosen in 3 years, 9 were women of color. Of course, it is possible that a few of the other women chosen could have been women of color who were not pictured, and whose race or ethnic heritage were not marked in the text in any way. It could be argued that the creators of the list were trying to avoid "spotlighting" the race or ethnicity of the women listed, but what is significant here is how the relative absence of women of color serves to silence their power, especially when there are so many pictures of white women in the articles. Whether by intentional or inadvertent exclusion, or due to adherence to a "colorblind" ideology, the resulting image created of a powerful professional woman is one in a white body. By examining the three "Power 50" lists, it is clear that the discourses of white supremacist, capitalist, patriarchy (hooks, 1995) are loudly and uncritically forwarded and celebrated by Fortune as normative in the business culture. The final area for analysis is the press coverage surrounding Carly Fiorina, the woman who has reigned as "Most Powerful" since the list's debut.

The Case of Carly FiorinaWhen Carly Fiorina was first chosen as the most influential woman in 1998, she was the leader of a division of Lucent Technologies. By the 1999 issue, she had been named CEO of Hewlett-Packard (HP) and was still number one on Fortune's list in 2000. Compared to many of the other women on the list, because she held the top spot, she figures quite prominently in the text and photographs of all three of the articles. Unlike many of the women on the list, however, Fiorina garners media attention outside the annual "ghettoized" coverage. Shortly after she was named CEO of HP, articles about her appeared in such publications as Time and U.S. News & World Report. Generally, these articles seem to enthusiastically report her success at "crashing through the highest of glass ceilings" (Greenfield, 1999, p. 72), and referred to her as having won "the highest position ever held by a woman in a Dow 30 company" (Greenfield, 1999, p. 72). Although Ackerman (1999) noted that in Fortune 500 companies, only 11% of the executive positions were held by women, Fiorina was dismissive of the issue, saying, "I hope that we are at a point that everyone has figured out that there is not a glass ceiling" (Ackerman, 1999, p. 44) and that her gender is "interesting, but it is not the story here" (Greenfield, 1999, p. 72). While Fiorina's denial of the glass ceiling appears in the second issue of the "Power 50," and her statement is characterized as controversial, no space is provided to other women on the list who might choose to counter her claim.

In contrast with the typical coverage of women in Fortune, the news magazines did not refer to Fiorina's appearance. U.S. News & World Report, however, could not resist discussing her familial status (especially her stay-at-home husband), and forced her into a "child" (Kanter, 1977) role with the headline, "Silicon Valley Girl" (and also aligns her with the ditzy, superficial, shopaholic image of the "valley girl" made popular by the Moon Unit Zappa song in the 1980s). Similarly, Fortune ran the story under the headline, "Fortune Cover Girl Storms Valley" and reported that she was a logical choice to head HP, because the company "needs a makeover" (Zesiger, 1999, p. 29). The Fortune story also mentioned one (and only one) of the key people who had also been considered for the job, Ann Livermore, who repeatedly denies being resentful of Fiorina, despite Fortune's efforts to conjure up a "catfight". Notwithstanding the Managing Editor of Fortune's claims of being committed to reporting on women, this story was only a few paragraphs long (compared to stories 3 or 4 times the length in the news magazines).

So, despite Fiorina's insistence that there is no glass ceiling, and that her gender is not relevant, she is portrayed in ways that are unmistakably feminine, as a "cover girl" who will give her company "a makeover." Her denial of gender and reluctance to be a role model for other women may be an attempt, made by herself and by media, in Trethewey's (2000) terms, to discipline her female body and fit into our construction of what it means to be "a professional." And she does, perhaps, have limited means with which to fight inevitable charges of "tokenism." But her silence on gender seems only to let others speak more loudly of her--and the media discourse about professional women, particularly in Fortune, does just that.

Unfortunately, instead of seeing how her success has been made possible by many other women who worked hard so that someone like her could stand on their shoulders, Fiorina retreats to the discourse of individualistic meritocracy. Given her stature in the business world and the media attention that comes with it, she is a role model whether she likes it or not. What if she recognized the many ways in which people who are not white, upper-middle class, heterosexual, and male are left looking through the glass ceiling? What if she could interrogate her own privilege and acknowledge the ways in which she has both benefited from and been challenged by the current system of social relations? What if she felt a responsibility, not just to herself and (temporarily) HP, but also to the broader community? In stark contrast to Buzzanell's (2000a) plea that we challenge the individualism of the "new social contract" and value connection, Fortune reports, "In her view, power flows to men and women alike who think of themselves as self-directed free agents" (Sellers, 1999, p. 126). Feminist scholars of organizational communication must find ways to challenge this prevailing discourse. We must work to redefine success as a relational construct, and acknowledge that our identities are not completely our own. By exploring how Carly Fiorina in particular, and businesswomen in general, are discursively constructed, it is my hope that we can change the conversations we have in, around, through, and about organization.

Conclusion: Reversal of Fortune?

My intent here is not to put inordinate blame on Fiorina and her discursive choices, nor is it my claim that she (and the other businesswomen) have been completely manipulated and controlled by the media. All of us (including men and women who are media professionals) have entered careers where the conversations were already in progress and the rules for participating were given to us. Instead of being trapped in current discourses, however, we must also realize that we have agency (Giddens, 1979) with which to alter them. Carly Fiorina, the rest of the women on the "Power 50" lists, and the producers of the popular business press are merely participants in the conversation. We can choose to reproduce the oppressive structures through our silence or our uncritical participation in the existing discourses, or we can question, challenge, stretch, and change the rules of the conversation.

And lest we communication scholars find ourselves feeling smug vis a vis the popular business press, one only needs to look to the Blair, Brown, and Baxter (1994) Quarterly Journal of Speech article for a critique of the male paradigm privileged by our own publications. For many reasons, Blair, Brown, and Baxter (1994) object to the publication of an article which listed "the most prolific active female scholars in communication, 1915-1990" (Hickson, Stacks, and Amsbary, 1989; 1992). One of their chief objections is the "yardstick" approach with which to compare female scholars to one another, that ignores the quality or context of the work produced. Among the many lists this research team produced, "females" were the only demographic or cultural group singled out and subjected to the paradigmatic male "yardstick." In addition, ranking women creates a hierarchy which invokes competition among the various listmakers, and also carries a negative implication for those not on the list.

It seems to me that these same criticisms could be raised with regard to the "Power 50" articles. Ranking women in business singles out women for inspection and measurement by a male yardstick, creates a hierarchy solely among women, and decontextualizes notions of power. Nowhere in the articles is it clear exactly how the ranking decisions were made, and the definition of "power" that is privileged is grounded in patriarchal organizational assumptions. Scholars should continue to resist such crass "rankings" of women and question how they are constructed through oppositional readings of such texts.

This paper attempted to examine how women's "professional" images are disciplined through the popular business magazine, Fortune, and posits that this form of media reflects, but also helps to shape, organizational reality. Beyond the critique of Fortune's "Power 50," there are broader implications of studies like this one that move beyond the normal boundaries of our subdisciplines in communication. In presentations of this research and during the publication process for this article, one not uncommon reaction from readers and reviewers is that "this is a mass com, not an org com problem," which I found to be a disappointingly narrow reaction and also an indication of the failure of my attempt to demonstrate what we already know: that organizations exist in a broader social world. I challenge us to position ourselves more often as disciples of communication (Shepherd, 1993), not only adherents of particular subdisciplines.

The blending of media criticism with organizational communication is just one way that this sort of boundary crossing can take place. Organizational communication scholars who have delved somewhat into rhetorical criticism, interpersonal communication, or intercultural study should be encouraged to continue doing so and their audiences should be more open to research that defies traditional scholarly boundaries. In addition, it would be interesting to see other connections grow and develop--perhaps in the intersections of interpersonal communication and media criticism, organizational communication and performance studies, rhetorical criticism and intercultural ethnography, or other infinitely possible combinations. Such cross-pollinating scholarship opens up a dialogue between perspectives and literatures that too often proceed without mutual acknowledgement.

Scholars interested in organization, in particular, also ought to continually question current organizational metaphors and create newer and fresher ways of understanding organization, rather than simply accepting what has been given. The outdated "container" metaphor that continues to hamper the ways organizational scholars talk and think and write about organization is implicated in the architecturally oriented metaphor of the "glass ceiling." The "glass ceiling" metaphor has been extremely useful in helping us talk about the subtle reasons for the lack of white women, women of color, and members of other marginalized groups at the top echelons of organizational life. However, it perhaps has also led us to focus too closely on what is going on "inside the organizational container" rather than seeing organizational boundaries as permeable and recognizing the ways in which the sociocultural environment (including the media environment) shapes and is shaped by organizational life.

The glass ceiling metaphor assumes what Carly Fiorina claims, that as soon as one woman "breaks through" the glass, then the ceiling no longer exists for anyone. This assumption is extremely harmful, as many organizations believe that they are doing enough to promote diversity if one token "glass ceiling breaker" is present in its executive ranks. Perhaps what we have been calling the "glass ceiling" is really more of a "transparent forcefield." As in science fiction, the transparent forcefield protects the people behind it, but the protected ones have the ability to deactivate the forcefield momentarily to let someone deemed as unthreatening pass through. Transparent forcefields can also be dynamic, moving at the whims of those it protects, unlike a glass ceiling that is bumped up against in more predictable ways. If the "transparent forcefield" metaphor does not catch on, perhaps metaphors like "hidden keys to the boardroom" or the "passcard to the executive washroom" are more appropriate. Scholars would do well to continue playing with new ways of understanding oppression in organizations and their environments rather than solely relying on previously overused metaphors.

In addition to the aforementioned recommendations for scholars, media practitioners ought to examine their practices and consider how coverage of women interacts with organizational life. So, what kind of coverage would be ideal? First, popular business magazines could begin to truly cover women as much as they cover men in business, and not relegate them to one issue a year. Second, they can avoid creating hierarchies of women that promote the sense that women should compete with one another for a few top spots and take the focus away from the continued existence of male dominance of U.S. corporations. Third, they could challenge white supremacist, patriarchal, heterosexist, and hypercapitalist notions about what counts as power to include a more diverse group of women in their list and in other reporting throughout the year. Fourth, they can use photographs of men and women similarly, and not use supermodel and housewife poses to display the bodies of businesswomen. Fifth, they can avoid stereotypical language and topics when reporting on women and treat them like the serious professionals they are. Sixth, they can make family concerns, sexual harassment, affirmative action, the glass ceiling, diversity, and other such issues regular features in their coverage of what is important to women AND men in business today, rather than relegating them to "women's issues" status. Finally, they can provide spaces for critique of the status quo in business, rather than just enthusiastically accepting the way things are.

Ironically, the cover of the third "Power 50" issue features quite a departure from the first two. The actual cover of the magazine highlights a completely different story and features a large facial shot of Michael Dell. There is an extra flap that fits over about 1/3 of the cover and advertises the "Power 50" list, with a few small head and shoulders shots of list makers.

While these cover pictures are much less stereotypical than the earlier two covers, they have been moved off the cover and to the margins (so to speak). It is doubtful that the editors of Fortune will automatically begin to speak a new language without being challenged, and it is my hope that this kind of scholarship can provide such a challenge and thereby assist in the transformation of the organizational discourses that currently constrain us. As long as the women who break the glass ceiling do so in a way that does not challenge patriarchal notions of organization or of gender--as long as they do so without breaking a nail--our discourses remain untransformed.

Works Cited, Author Note, & Footnotes

Back to Top

Home | Current

Issue | Archives | Editorial

Information | Search | Interact