|

|

|

|

|

![]()

Volume 5,

Issue 2, Winter 2002

|

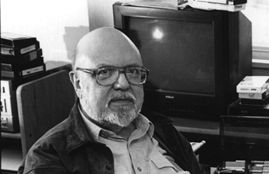

Meet Your Footnote: Gerald Phillips

|

by Michael

Calvin McGee photo by J. L. Lucaites |

Printer-friendly PDF version

Want to nominate someone for a future issue? Add to these memories with some of your own? Or "correct" Michael's memory? Jump over to Interact

Errors in my first column? Unmistakable, irretrievable, wholly embarrassing, blush-red errors in my first "Meet Your Footnotes?" Flo-Beth Ehninger, an old friend and Douglas's widow, wrote to say "I ran across your piece on the Internet, in the American Communication Journal, and enjoyed reading your kind words about Doug as well as the 'Meet your footnote' bit. Thank you for refreshing my memory." Then she refreshed my memory, gently as always: "It is not a world-shaking matter that the biographical material contains slight deviations from the fact, but I will tell you about them in case you are interested." By now, the "in case you are interested" has me gulping the way I used to gulp at prods and pointers in Professor Ehninger's seminars. Can the ability to produce "the gulp effect" run in the family? Sideways in the family, from spouse to spouse? "We were raised as neighbors not in Ft. Wayne, but in Michigan City Indiana. Doug had a Ph. D. from Ohio State U. However, he had a bachelor's and master's degrees from Northwestern U."

Whew! Thank goodness my errors had no effect on my encomiastic narration. Professor Ehninger is no less imposing a footnote for the 80 miles or so from Michigan City to Fort Wayne, and in terms of one's Big 10 pedigree, the difference between Northwestern and Ohio State is immaterial. Factual errors need correction, however, even in myth and lore. Thanks, Flo Beth!

Our focus in this column is Professor Gerald Phillips, the gruff, earthy, powerful, legendary footnote who held forth for decades at Penn State University. This is a longer column than usual because Buddy Goodall (AKA @#$%$ GOODALL!!!! and H. L. Goodall) has written a tender, funny, respectful tribute to his former teacher that deserves your attention in its entirety. Because we are digital at ACJ, we can afford longer pieces, especially when they come from one of our field's finest ethnographic narrators and concern one of our field's brightest stars. We have five Meet Your Footnote stories here, told in order of passing through graduate school at Penn State during the Phillips years. What is it like when you not only meet your footnotes, but also have to live with them? Let's listen to Buddy:

|

As a new doctoral student in the Department of Speech Communication at Penn State back in 1978, the name Gerald M. Phillips was already well known to me. We had used his small groups text in a class I took at Chapel Hill and I had taught from one of his co-authored speech pedagogy texts at Clemson. I had read several of his essays in our journals and knew him to be deeply involved in a variety of ongoing scholarly conversations-shyness/reticence; speech pedagogy; small group/organizational communication; interpersonal communication; rhetoric. I looked forward to meeting him in person. I am not sure what I expected him to look like. Given his scholarly stature, I am sure I thought he would be tall. Probably imperially thin. Most likely athletic. Gerald M. Phillips sounded like the sort of name a Bostonian might have, or maybe someone from the big city of Chicago. I no doubt also attributed to him a variety of other fine qualities that, if the truth were known, I somehow associated with the cultural mystery of a doctoral degree and wanted myself desperately to acquire. "You Goodall?" This query, spat out like a curse, sprang up at me from a very short, very fat, very bald man with a Freudian goatee holding a huge unlit cigar, and whose round eyeglasses so enlarged and magnified his bloodshot eyes as to make it seem as if he were either experiencing great pain or was quite insane. I was immediately afraid of him. I stepped back. |

|

He grimaced. "Buddy Goodall?" He laughed. "You're kiddin' me, right?" He sounded like a thug. One of those B-movie characters who "packed heat" and said things like "now 'dis is what we're gonna do." I figured he must be Someone though, as we were standing on the second floor of the Sparks Building, which was home to the Speech Communication and Philosophy departments. He did not sound like a philosopher. I hoped he was not a Communication professor.

Still reeling from his question and suddenly off-balance in my presentation of graduate student self, for a moment I wondered if I had, in fact, become someone else. There was like a five count during which time he lit his cigar. Billows of pungent gray smoke covered both of us.

Seeing that I wasn't kidding, he planted the stogie firmly in his mouth and rechecked the folded sheet of typed paper in his small, almost delicate, hand. "Says here your name is Harold. Now that's a good English name. Harold Lloyd Goodall, Jr. Named after your old man who himself was named after that great silent film comedian. Am I right?"

I nodded.

"So what's this 'Buddy' shit? Your mother knows you call yourself that?" He sounded bemused, not mad. I saw what I thought was a twinkle in his eyes. He was joking with me. At least, I thought he might be joking with me.

I decided to play along. "Naw," I said, mimicking a tough-guy attitude, "I keep it from her. I'd be in big trouble if she knew." I smiled.

"You're already in big trouble, kid," he replied. He stormed off in a sudden hurry, trailing smoke and my failed answer behind him.

"Who was that?" I asked no one in particular. "Jesus Christ."

A female voice from behind a partially open door replied: "No. That wasn't Jesus Christ. That was Gerald M. Phillips." There was a pause. "He only thinks he's Jesus Christ." She laughed. Her door opened and Jeanne Lutz smiled at me in a conspiratorial way. "Don't tell him I said that," she winked

I am a tall man-six feet two-and there is nothing wrong with my hearing. I say this because every time Phillips saw me-from that first memorable day through the successful defense of my unique dissertation (which he co-chaired)-he screamed at me as if addressing one of the deaf from a great distance.

"GOODALL!!" he bellowed. Even now, from the distance of these two decades, I can still feel the echo.

He had, by midterm of my first year, sworn off smoking-this in an era when almost everyone still smoked something in their offices, in the hallways, and during meetings. He had posted a large, unambiguous "NO GODDAMN SMOKING!" sign on his office door, and agreed, somewhat grudgingly I thought, to become my temporary doctoral advisor. His rules were two: (1) No grades lower than a B, or else find another advisor, and (2) no missed deadlines on anything assigned to me to be read or written, or else find another advisor. I had not earned my first term's grades yet, so I was still only worthy of "temporary" advisee status. I would never miss a deadline. That day he gave me my first two "outside reading assignments": Baldassare Castiglione's The Book of the Courtier and another tome whose author I cannot now recall but whose title I can; it was Life in a Medieval Castle.

He explained that he was preparing a manuscript on graduate education modeled on medieval courtship and my insights on symbol usage would be appreciated. But I knew what he was also saying. I read these books for their symbols as well as their value as signs. I was still in greatly deferential graduate student mode and therefore was on my very best graduate student behavior. If I were a dog, I would have been a Golden Retriever.

On this day, however, he was standing by his bookshelves, which, five rows deep, ran the length of his office and were jam-packed with books, journals, and the occasional frog. Phillips, I had learned, was a widely read scholar whose intellectual interests spanned most of the humanities and all of the social sciences, as well as popular self-help volumes, computers, and the operas of Gilbert & Sullivan. He was educated in classical rhetoric, and he once served as Hebrew language instructor at his synagogue. By the time I knew him, he had abandoned religion and rhetoric but not their sacred texts. He was studying for a role as a King in some Shakespearean play on campus, had appeared on the Johnny Carson show for helping his students invent and disseminate a word that actually made it into the dictionary, and, as I stood there awed by all those books and his obvious learnedness and accomplishments, I noticed there was also phone message on his desk asking him to return a call to Shere Hite. He had, by that time, published twenty-something books and god knows how many articles and papers. In class, he was a thoroughly prepared and incredibly well organized master teacher who cross-referenced Everything and made sense of It All. I, like most students, wrote down every word he said. He was 49. I was 25.

"Goddamn it, Goodall, are you listening?" When angered, his eyebrows could literally travel upwards into his forehead at an alarming rate. In part this was fueled by his recently-acquired habit of chain-eating Espresso beans, probably an oral substitute for chain-smoking those stinking cigars.

"Yessir," I replied. Lynne Kelly, David Sours, and Bruce McKinney sniggered, but even so, I could tell they were sympathetic to my courtier's plight. They had won the prized desks at the Court of Sir Gerald O'Nitny ; they shared his huge office space and worked closely with him on shyness research. They were also advisees, but more importantly, they ran what was, at that time, the nation's only full-time Shyness Clinic, something Phillips created long before it became fashionable and it served as a major source of personal gratification for him. He loved to see the personal transformations that took place when a young woman or man learned to overcome severe communication apprehension.

"Know what Ernest Becker says we humans are?"

I had never heard of Ernest Becker, and maybe he knew that, so I said, "no, sir, what are we?" "Angels with assholes," he replied.

"Angels with assholes! Goddamn, that's a great line!" He was tickled. He handed me an armful of Becker paperbacks. "Here, go home and read these."

I accepted the books. I was afraid to ask the question, but I had to: "What do you want me to do after I read them?"

"Write a paper for me in the next two weeks on Ernest Becker's contributions to communication theory," he said. In my head I was squeezing this "outside" assignment in between the paper on rhetoric for Hauser and the paper on semantics for Pedersen and grading the two sets of speeches for the public speaking courses I was teaching.

It never occurred to me to say no.

It never occurred to me to tell him all the work I had to do in my other

classes.

It never occurred to me not to live up to his standards.

This was the Court of Higher Education, Sir Gerald O'Nittany was my teacher. I never made excuses because I was the one who was asking for an education. No, better-I was asking for a life of the mind, for cultural sophistication, for a scholar's lifestyle that featured reading books, writing papers, teaching classes, talking about ideas with smart people, and doing something with my life that mattered. I wanted to make a contribution to knowledge. A damn fine contribution.

I did not know what my damn fine contribution would be yet, I just knew that I wanted to make one. This was where I belonged. Where better to learn what that would be, and how to do that, than with a man who had done it, and was doing it? He was not an easy man, and this was not an easy life, but as I left his office that chilly winter's day, I let go my breath and surrendered to both of them.

The time was rapidly approaching for us to talk about serious things-serious in the reified context of higher education: the composition of my doctoral committee, a formal plan of study, research interests, and possible dissertation topics. I had more or less let it be known that I thought of myself as a writer, which made me a little unusual among my peers, which I liked. But the truth was that I wasn't a very good writer. And I knew that, too.

"GOODALL," he screamed up at me. He was eating a homemade dieter's lunch at his desk-some black olives, some green olives, a few sticks of celery, some baby carrots-on orders from his physician, who had told him that he had less than two years to live if he didn't dramatically change his lifestyle and bad habits. Phillips loved his lifestyle and his bad habits. He was a dedicated workaholic who also fully enjoyed food, drink, music, jokes, poker, and the good life. This news of his impending death scared him enough to change him, forever. He started exercising and dieting, bringing to these new habits the same old energies he had brought to his bad habits. Watching him eat lunch, even a light lunch, was tiring. His bare hands attacked vegetables as a fundamentalist preacher's bare hands might attack the necks of choir members discovered fornicating. His mouth was a place of pure pleasure mixed with obvious sensual delight. He chewed, bit, sucked, slurped, and licked every bit of flavor he could find out of every single Greek olive or cherry tomato. Throughout this process of conspicuous oral consumption, he talked nonstop while making notes on something he was reading.

"Yeah," I responded. I had lost most of the formality of properly uttered English usage, graduated I guess from one level of rhetorical courtship to another, less rule-governed one, and now found myself free enough in his presence to be more amused than frightened when he bellowed my name.

"What do you want to be?" He said this with all the ease of having said something far less important, so at first I was not sure if this was an invitation to something serious or just a joke.

"Rich and famous," I replied.

"Good. Then drop out of school now and go into investment banking." He did not look up or sound upset. He kept right on munching, scribbling, munching, scribbling. I laughed because now I was embarrassed and nervous. I stopped laughing when he turned his full attention on me and said, "well?"

"Well what?" Now I was just embarrassed.

"What do you want to be?" He shrugged. He could shrug better than any man I've ever known. It was full-bodied and at the same time capable of carrying a variety of subtle and nuanced meanings. The one I was witnessing was somewhere between "if you can't answer the question get out of my office" and "suit yourself."

"I want to be a writer," I managed.

"Yeah, I heard," he replied. Munch, scribble. "So what do you want to write?"

I knew what I was supposed to say, or at least I thought I did. I was supposed to say that I wanted to write either elegant social science or artful rhetorical criticism. But that was not true. I wanted to write novels and short stories. I had imagined myself as a writer with a Pee Aitch Dee who could use the knowledge I was gaining in graduate school about human communication to construct better stories, richer conversations. I had never said so to Phillips before. And I did not say it then. Instead, I said this: "I want to write stories that people will read and that will change their lives."

The audacity of it surprised even me. But Phillips was truly interested now. He stopped eating and scribbling and turned his full nonverbal attention toward me. He seemed to be appraising what I had said. Probably he was testing against his internal bullshit detector. Finally, he said, "Hmmm."

I then launched headstrong into a seasoned debater's defense of this never-before articulated position, saying wild and fanciful things I'm sure, half-baked and even stupid things no doubt, statements and vague utterances I wish I could now recall if only for the hilarious descriptive details, but I can't recall them, which is another way of saying that I was filling up the available space with orality and verbal noise, as if to put a little time between what I had just blurted out and whatever it was that would come from it. Phillips listened intently to this earnest but totally spontaneous and probably nonsensical soliloquy. Finally he said, simply, "well, then, I guess we'd better get you into some writing classes."

"Writing classes?" I thought I had misheard him.

"Yeah, writing classes. Let's see if you can write."

"See if I can write?" I repeated. I had gone from effusive to imbecile in less than a ten seconds.

"That's what I said. You know the old story about Abe?"

"No," I said. "Abe tales" were standard Phillips' stuff. It was his way of signaling a Yiddish tale. Each tale had analogic content. This was also a Phillips performance opportunity and he seized it with all the veiled enthusiasm of an old actor called back onto the stage.

"So Abe gets himself rich and buys himself a brand new boat. A big boat. A yacht. And since he's got the big boat he buys a nice, big Captain's cap." Phillips placed an imaginary cap on his own bald head. "Puts on his big Captain's cap, takes his dear old Mudda down to his brand new boat and says, (here he gestures, grandly) 'see ma, I'm a Captain.' His Mudda says, 'yes, my son, but among other Captains are you a Captain?'" He grinned, wide, opened his arms to imagined applause, performance over. "See Goodall, you may think you are a writer, may even want to be one, but let's let some other writers see what you can do. Let' see what other writers say. Okay? Fair enough?"

"Okay," I replied. "Fair enough." Part of me was soaring to wide blue writerly heights and the other part was descending rapidly into a dark personal abyss. I seemed to be engulfed in a long echo made from the awful stuff of my own internal silences. I gulped. "Who should I take?"

He did not hesitate. "Stanley Weintraub." He went back to his lunch, picked up a last surviving Calamata olive and placed it lovingly into his mouth. "Weintraub's a biographer, runs the Institute for Humanistic Studies next door. He's written a lot of books, won some big literary awards. Gets reviewed in the New York Times. A real pain in the ass, but good. Real good. You'll go see him today, ask him if he'll let you in to his biographical writing class this semester."

He chewed the last olive so long that I finally swallowed for him. "Why biography?"

He shrugged, fully. "Why not?" He squinted at me. "What's da matta, you don't like biography?"

"I had sort of thought fiction." I said it mildly, without a lot of determination.

"Fiction comes later." He held up his left hand, as if to stop or at least block my words. "Let's see how you do writing about real people first. If you are any good at that you can do the other over the summer, or even next year. Like Aristotle said, 'first mathematics, then philosophy.' There's an order to everything in the universe, Goodall." He closed the plastic lid on his small lunch container.

"Besides," he offered, "the news isn't in fiction anymore."

The news may not have been in fiction, but Phillips always claimed he was writing a great novel. "It's epic, Goodall, it's epic I tell ya," he would declare when I asked what it was about.

I thought a novel was an imagined kind of book, not an imagined kind of life. But the more I got to know Phillips, the clearer it became to me that his life was indeed his great art. Each day he awakened not as a strictly empirical person, but as a repertoire of dramatic personae. His theatrical imagination, his historical and psychological knowledge, his operatic musical appetites, his ability to perform ethnic accents and regional dialects, his love of vaudeville humor-all of these raw materials produced genuine characters he deployed into the everyday in much the same way as a fine fiction writer deploys characters in every chapter. Phillips' day was a continuous epic work in progress, as he moved his highly rhetorical figures through conversations and situations with us lesser empirical souls, placing us into the role of readers of multiple meanings as these characters-Sadie the sales clerk, Sam the social scientist, Abe the ne'er-do-well Yid, Polly the "poil of a goil," Perfessa Learned B'God, a myriad of figures borrowed from Gilbert & Sullivan, and most the of the cast on loan from The Muppets-spun out their little dramas and collectively constructed his finest public work, his true epic "novel."

There was, in addition to making that part of my life with him interesting and rewarding, a great ethnographic gift as well as many interpretive lessons in his daily performances. Beneath all the banter and play was the serious idea-probably too serious to be spoken any other way-that who we were existed (perhaps only existed) in relationship to others, and that our job-as persons-was to help make that relationship interesting and rewarding each and every day. Contained within this idea was the critical methodology of its accomplishment, or the realization that communication was the only available methodology for constructing everyday life. And then there was this left-handed gem: That who we were when we observed, conversed with, experienced, and otherwise related to others mattered to what truths we found there, and to we said about it, in the same way as the positioning of a fictional observer mattered to Heisenberg's eternally uncertain empirical universe.

If you have read any of my autoethnographic work, you now know my teacher.

He may have sent me to Stanley Weintraub, or then to Phil Klass, or even after that to other Professors of Creative Writing to test and refine my narrative skills, but he was giving me a personal tutorial in the ethnographic imagination.

My comprehensive examination oral was an hour away. If you have been a doctoral student-no matter how well or poorly you thought you had performed on the writtens-you know this hour is to be endured as a deep and private hell.

There is no longer hour in all academe. Not the dissertation defense, which, if it gets to a defense, is hardly worth its label as the decision had already been made. Surely not the tenure decision, either, as only a fool enters that year with any degree of uncertainty. No, it is the comps oral defense that is the most neurotic of all the otherwise dysfunctional moments in academic culture.

"What d'hell's wrong with you?" Phillips asked. I was standing in his office anticipating all the things that could go wrong in our meeting, now just fifty-eight minutes and forty seconds away. He knew what was wrong with me. I knew he knew.

"Nothing," I lied.

He shook his head as if dealing with someone-me, namely-who had just demonstrated that he was both a liar and a fool.

"Bullshit," he replied. He yawned. Maybe another two minutes passed as only slow minutes do, tick by unmitigated tock.

"Goodall, let me ask you question." It was not a question, so, still unraveling inside my personal neurosis, I nodded to him as if he needed my assent.

He stared up at me. I was still tall. "You got a friend?" he asked. His voice was, for once, not ironic or comic, just mildly curious.

"Yes," I said. My pal Stewart came immediately to mind.

"You got a car?" He asked this one in the same mildly curious tone.

"Yes, you know I do." Which was true, although he had refused to ride in it on the grounds that it was French. It was Renault R-17 Gordini, at the time a cool sports car. I could have been offended by his refusal but we both knew the obvious truth: The real reason he would not ride in it was that once his body was positioned that low in the passenger seat he feared he might not be able to get up again with any degree of grace. I began to smile at the memory.

"You got a dollar?" Now he was up to something. He never borrowed money. He would ask, just to see if you would lend it to him, but he would never accept it.

I reached into my wallet, checked its meager contents, and said, "Yeah, I do. Why?"

He took a deep breath and let it out slowly. "Then Goodall, what the fuck are you worried about?"

He was right, of course. What did I have to worry about, if all that I had to worry about was answering a few questions posed by well-intentioned men who were my mentors? Let's put life into perspective. I had a friend, a car, and a few dollars.

Everything else was easy.

In 1980, the year in which I completed my dissertation, there was no ethnography going on in the Speech Communication department at Penn State. In fact, there was little ethnography going on in our discipline outside of Gerry Philipsen's group at the University of Washington and some beginning conversations among organizational studies scholars at the University of Utah. Tom Benson, in our department at Penn State, was on the verge of publishing his infamous piece of QJS ethnographic new journalism called "Another Shootout in Cowtown," but I did not know that. Benson and Phillips were foes and I was not allowed to take a course with Benson. I have often wondered what might have happened if this unfortunate fact of their relationship had not been so obviously true.

In some ways, it would not have mattered. By the time I had assembled my graduate committee and given them an initial proposal-the outrageous (and I think, in retrospect, smoky) goal being to test existing theories of communication in Thomas Pynchon's novel Gravity's Rainbow-I had decided that I was mostly a rhetorical critic and a large fan of Kenneth Burke. My covert plot was to find a way to do rhetorical criticism of fiction, which, again, at that time and in that place, was at the outer limits of scholarly eccentricity.

Phillips had a different vision for me. He was a skilled negotiator, as well as my doctoral advisor, so I have never been sure if he got his way because I was relatively powerless or because he was curiously right-minded. Our discussion went something like this:

"I've been thinking about your dissertation." He said this in the same style you might expect from a car salesman when he is about to tell you how little your trade-in is worth.

I nodded. "I still think the first idea was a good one." I did, too. I was just wrong. If we were negotiating the value of my trade-in, this would represent a stubborn response and what I was about to say would constitute a weak counteroffer. "Maybe if I redo the proposal and tone it down a bit . . ."

"Goodall," he broke in. "Nobody on your committee wants to read that fucking novel. It's that simple." He shrugged. There was no room to negotiate. "You are gonna hafta find something else to do."

I sat down. I really wanted to graduate this year.

"Weintraub says you ought to do a biography." He looked at me, evenly, gauging my response. There was not one. I was still lost in my own head. "Weintraub says he'll agree to co-chair it." I heard that, though. This was news.

"He said that?" I was more than hugely surprised. Weintraub and I had gotten along well enough, but . . .

"He said that." Phillips got up and paced around the office. He was wearing a white-on-white dress shirt, thick red suspenders, loose navy blue slacks, and red Converse All-Star tennis shoes. He had dropped about fifty pounds on his diet and exercise regimen, which brought his 5'5" frame down to about 250. He had on a beret, a black job that he told me belonged to his revolutionary uncle, a man famous in Cleveland for accidentally blowing up his own deli. He still sported a goatee, which made him resemble a bloated Trotsky.

"He liked the paper I did on Scott and Zelda (Fitzgerald)," I recalled.

"He told me." Phillips was thinking, circling, thinking. "I think there might be something there," he smiled. "You want to test something on a work of fiction, right?"

"Yeah," I replied. "I do. In my paper I framed the biography as a way to understand interpersonal issues in their lives, and how these issues were either derived from, or contributed to, their fiction."

Phillips stopped and snapped his fingers. "That's it!" His eyes lit up, pushing his eyebrows into the nether reaches of his forehead. "Do that, only bring in some of that Burke shit." He continued pacing, right out of the room.

Burke shit? I had to smile. Phillips often derided my interest in Burke, not because he did not think Burke was important, but because he didn't like what he called "textual exegesis" to count as original thinking. In his view, most of what passed for Burkeian scholarship was textual exegesis. Some years later, Burke himself would address us in Philadelphia at an Eastern Communication Association conference and accuse us of much the same thing.

He returned a little later. "Herm (Cohen) thinks that will work, and so does (Dick) Gregg," he announced. These were committee members and he had been to see them. "Now what have you come up with?" He sat across from me and put his feet up on the table, his red tennis shoes crossed at the ankle.

"Courtship," I said. "Remember that piece I did for you about Burkeian courtship?" I knew he remembered it; he had used it in an essay published in Communication Education.

"Yeah," he said, "so what? So what does courtship have to do with a biography of Scott and Zelda?"

"I don't know yet, I just know it does." Which was true. In my head I had invented some connection that felt right, even if I didn't know how to articulate it yet.

"Go away," he said. He did a "shooing" motion with his hands. "I want a proposal on my desk by the end of the month."

I went away. I wrote the proposal, then the dissertation. I got a job, got married, got moved. It was proud day when he presented me with his personal diploma, a colorful pen-and-ink drawing in a medieval style entitled "Advice to Writers." The advice? Avoid Sesquipedelianism. Attenuation. Prolixity. Floridity. Concupiscence. Self Abuse. Circumlocution. Exhortation. It was signed, Gerald O'Nitny.

I still am not entirely sure I know what it means. I only know I'm proud to own it. Proud to have earned it.

Phillips and I went on to write together and gradually became friends. He told me that he never was a friend with graduate students until they graduated, nor wrote anything with them, until they graduated. He believed the power imbalance left no room for equity, and he was big on equity in all relationships. This was his rule and it was fine by me. Friendship and co-authorship had to be mutually earned, and then they had to be mutually nourished.

"Goodall, I'm dying." I recognized the voice, no longer capable of booming. It was old, frail, fearful. Where once vibrant and green it had softened and yellowed.

What he said was true, even though he had been saying it for years when it was not yet true. But he said it now and I knew it was true but could not admit it. He knew it and did admit it but intensely hated it. Neither of us did death well.

Maybe none of us really do.

There is a long circular echo from that last phone call, from that last farewell, that lives inside of me. I can hear all of the years we talked together in it. It blossoms him back into life, enlarges the ordinary in him to extraordinary metaphors and meanings and then bursts, just like life does.

There are many gifts that a great teacher gives, but the best of these-and surely the hardest-is the gift of honoring originality and difference. When I met Phillips I was a young man who was not yet a writer but who wanted to be with all my heart. I was not like other graduate students in our program, who, all nevertheless distinctive and original in their own ways, identified closely with established scholarly traditions. I was not sure what I identified with, only that I needed a place to create it in. A mentor who would help me see some options. Someone I could trust to guide me.

Phillips gave me that.

He never asked me to conduct research, or to write, like he did. Instead, he encouraged me to grow my own voice. It took years to do that, and I'm still working on it, but it would have taken less than five minutes for him to have reduced me back then to a lifetime of disciplined silence. He did not do that. Instead, he offered me his hand in freedom.

Back to Top

Home | Current

Issue | Archives

| Editorial Information

| Search | Interact