|

|

|

|

|

![]()

Volume 5,

Issue 1,

Fall 2001

Mediated

Rhetoric: Presentational Symbolism and Non-Negation

Jon

Radwan

|

Printer-friendly PDF

version |

Department

of Communication Seton Hall University 400 South Orange Avenue South Orange, New Jersey 07079 radwanjp@shu.edu 973-275-2170 |

Rhetoric has been classed as a linguistic art since the beginning of Western culture, and the discursive tradition of rhetorical theory remains dominant today. This dominance is so strong that the rhetorical functions of non‑linguistic communication are routinely interpreted with a vocabulary borrowed from theoretical models designed to explain discourse, if they are addressed at all.[1] More commonly, work bringing a rhetorical perspective to non‑linguistic symbolism is defined as the proper subject of distinct specialties ‑‑ Cultural Studies, Performance Studies, Visual Media, and so on.

This essay contrasts linguistic symbolizing with mediated forms of rhetoric. My basic thesis holds that, while language and the arts are both influential forms, their symbols operate in significantly different ways. Discursive meaning arises through difference within a system, whereas artistic meaning is based on a more basic (less systemic) spatio-temporal presence. In today’s mediated world, rhetorical theories that do not recognize this distinction cannot enable us to effectively interpret and participate in social exchange. By exploring the differences between discursive and presentational symbols, we can begin to develop a vocabulary that describes non-discursive rhetoric without the linguistic assumptions built into the rhetorical tradition.

There are four major divisions to this essay. After an introductory definition of terms, Kenneth Burke’s conception of The Negative is discussed as a fundamental feature of language. Next, Suzanne Langer’s Presentational Symbol provides a theory that can account for the arts and media — symbolic forms that communicate without negation. Finally, music, architecture, and painting offer specific case studies in how the arts generate meaning without depending upon an implicit or explicit “No.”

Definitions: Rhetoric and Media

In this essay’s title, Mediated modifies Rhetoric. Accordingly, we should define the genus before proceeding to the species. Rhetoric, then, denotes the process of mutual influence that characterizes social exchange. It is the basic human process, in the sense that we are social animals who necessarily look to one another for cues on how to continue living as members of a community. Whether this community is a family, a tribe, a village, a nation, or any other group, it will possess its own characteristic way of life that is perpetually re-constituted in the daily actions of its people. The continuation, development, and growth of this social pattern is ensured through the rhetorical processes of communication.

This definition is deliberately Burkean in its breadth. It applies to the influential element in all social intercourse, not only the purposive and intentional focus of the rhetorical tradition. Burke introduces his A Rhetoric of Motives with this description of rhetoric’s broad scope:

All told, persuasion ranges from the bluntest quest for advantage, as in sales promotion and propaganda, through courtship, social etiquette, education, and the sermon, to a “pure” form that delights in the process of appeal for itself alone, without ulterior purpose. And identification ranges from the politician who, addressing an audience of farmers, says “I was a farm boy myself,” through the mysteries of social status, the mystic’s devout identification with the source of all being. (xiv)[2]

My definition of rhetoric departs from Burke in its approach to our second key term, Media. As Burke’s thought developed over time, he gradually moved from Dramatism, the Philosophy of the Act, toward Logology, the Philosophy of the Word (and words about words). The line between these two frames of reference is not clear, largely because Burke’s critical work dealt with linguistic action throughout both periods. In pentadic terms, the shift is from Act to Agency, with language as his ultimate and defining means of human communication.[3] With Logology, Burke approached language as a motive in itself and stressed the characteristic ideas that this medium is suited to express — the negative, hierarchy, and a separation from the natural condition (40).

This essay would extend Dramatism by casting language as a human medium, rather than the human medium. If we define Media simply as that which enables communication, humans as symbol using animals take on a significance far beyond their linguistic ability. In A Grammar of Motives, Burke states his position clearly:

Our five terms [the pentad] are “transcendental” rather than formal (and are to this extent Kantian) in being categories which human thought necessarily exemplifies. Instead of calling them the necessary “forms of experience,” however, we should call them the necessary “forms of talk about experience.” For our concern is primarily with the analysis of language rather than analysis of “reality.” Language being essentially human, we would view human relations in terms of the linguistic instrument. (317)

This passage is certainly not “wrong,” but it clearly valorizes language over other symbolic expressions. Kant thought that he could describe forms of thought; Burke limits himself to describing language as it forms thought. This is a very important move, (without it we might continue arguing about reality without considering mediation at all) but it does not extend far enough. True, the other animals do not write, but they also do not draw, or sculpt — a complete study of human relations sensitive to media should include our other essentially human instruments; the brush, the baton, the body, and so on throughout all of the arts and their special means of expression.

If we accept that all media may provide forms of thought about experience and reality, we can begin to appreciate McLuhan’s radical emphasis on the constitutive function of media. By enabling humans to “extend” themselves into the social environment in diverse ways, our different communicative media both invite and provide a means of articulating the ideas expressible within each particular medium. “All media work us over completely. They are so pervasive in their personal, political, economic, aesthetic, psychological, moral, ethical and social consequences that they leave no part of us untouched, unaffected, unaltered.” (McLuhan and Fiore, 26)

In sharp contrast with Burke’s logocentrism, Henry W. Johnstone casts mediation as the essential human action.[4] Instead of The Word, he uses our ability to reflect on and formulate experience to develop his “bi-lateral” ethic for communication.

Man is the mediating animal, the animal capable of reflecting on his own experience and thus of holding it at a distance. (While the [bee’s] honey-dance indicates the distance of the pollen, it does not hold the pollen at a distance, it simply triggers a response.) Furthermore, a person is humanized or maintains humanity if he or she addresses the capacity of another to mediate. (98)

Johnstone’s “mediating animal” would not be that much different from Burke’s “symbol-using animal,” if Burke did not repeatedly equate “symbols” with “language.” Because Johnstone takes the more abstract approach he is able to arrive at a social essence for humanity — we are or become human through engaging other humans. Burke, focusing more narrowly on the medium of language, derives a linguistic essence for humanity that skews his description in terms of the singular properties of discourse; the negative, hierarchy, and division from nature.

The Negative

One of the defining characteristics of language as a medium is its power to express the Negative. Many theories of language feature a negative principle as a basic component of discursive meaning. For instance, Structural Linguistics requires different elements related within a system in order provide a repertoire of possible responses.[5] Littlejohn explains that:

The key to understanding the structure of the system is difference: The elements and relations embedded in language are distinguished by their differences. One sound differs from another (like p and b); one word differs from another (like pat and bat); one grammatical form differs from another (like has run and will run). This system of differences constitutes the structure of the language. . . . No linguistic unit has significance in and of itself; only in contrast with other linguistic units does a particular structure acquire meaning. (73)

This Saussurean principle is the basis of Derrida’s famous theory of différance. He explains that, with language, “the signified concept is never present in and of itself, in a sufficient presence that would refer only to itself. Essentially and lawfully, every concept is inscribed in a chain or in a system within which it refers to the other, to other concepts, by means of the systematic play of differences.” (125)

Kenneth Burke approaches the Negative from a different angle; he cites Korzybski’s recommendation to “discount” language because words are not the things they denote. “The paradox of the negative, then, is simply this: Quite as the word ‘tree’ is verbal and the thing tree is non-verbal, so all words for the non-verbal must, by the very nature of the case, discuss the realm of the non-verbal in terms of what it is not. Hence, to use words properly, we must spontaneously have a feeling for the principle of the negative.” (1961 18) Burke goes on to extend the negative principle far beyond Korzybski and the General Semanticists by making language itself a primary human motive. First, he places the negative in the realm of human relations — “Dramatistically (that is, viewing the matter in terms of ‘action’), one should begin with the hortatory negative, the negative of command, as with the ‘Thou shalt not’s’ of the Decalogue.” (20) From here, our linguistic ability to conceptualize a pure and abstract “DON’T!” begins to pervade all human thought:

. . . [T]here is always the possibility that, if language does lead ultimately to this generalized use of the negative, the implications of such an end are present in even our ordinary thoughts, though in themselves these thoughts possess no such thoroughness. That is, though they are far from taking us “to the end of the line,” they may imply this end, if we were but minded to follow them through persistently enough. (22)

Of course, Burke does follow the implications of linguistic symbolism through persistently enough — he pushes the negative principle out of its proper place as an important linguistic concept and makes it the defining human concept.[6] In his Definition of Man, he posits that

Man is

the symbol-using (making, mis-using) animal

inventor of the negative (or moralized by the negative)

separated from his natural condition by instruments of his own

making

goaded by the spirit of hierarchy (or moved by the sense of order)

and rotten with perfection. (1966 16)[7]

Rhetoric, the process of social influence, goes on in many modes. Language is one, but there are many other equally human media, and they each have their own unique expressive potentialities. Despite Burke’s recommendation, there is no reason to grant language dominance among media. In Ways of Seeing, John Berger opens with an opposing argument for the priority of vision. “Seeing comes before words. The child looks and recognizes before it can speak. But there is also another sense in which seeing comes before words. It is seeing which establishes our place in the surrounding world; we explain that world with words, but words can never undo the fact that we are surrounded by it.” (7) An equally strong argument could be presented for the priority of rhythm and hearing. The child’s prenatal experience is governed not by words or vision, but by the continuous pulse of its mother’s heartbeat. My point is not that any of these arguments are mistaken — on the contrary, Burke, Berger, and the Prenatal Audiologist all have valid points to contribute — my point is that reducing human complexity to the forms of thought enabled by any single medium is a mistake. A discussion of Presentational Symbols can detail how the non-discursive arts generate meaning without relying upon the negative.

Presentational Symbols

There is an essential difference between words about experience and experience itself. The word is necessarily not the thing it denotes, and so linguistic experience always has an element of abstract detachment to it. Other symbolic forms are expressive at a more primordial level of experience, where things are necessarily only themselves. This fundamental presence of art is John Dewey’s basic position in Art as Experience:

Meaning does not belong to the word and signboard of its own intrinsic right. They have meaning in the sense in which an algebraic formula or a cipher code has it. But there are other meanings that present themselves directly as possessions of objects which are experienced. Here there is no need for a code or convention of interpretation; the meaning is as inherent in immediate experience as is that of a flower garden. (83)

For Dewey, art is experience. The successful work of art presents the sensitive beholder with a unified experience that is meaningful on its own terms.

Suzanne Langer develops this same line of thought in Philosophy in a New Key: A Study in the Symbolism of Reason, Rite, and Art. For her, symbolizing is the fundamental human cognitive process; whatever we encounter must be transformed into symbols if we are to deal with it at all. Symbols fall into two general classes, Discursive and Presentational, and human activities, while typically involving both, are given form through their reliance on one sort over the other. A dominant form of discursive action is languaging (including all we do with words, especially knowledge production and transmission), and presentational form is foremost in art and ritual.

With language (and all other discursive symbols, such as numbers), the form is linear and thus spatial. Because linguistic symbols must be used successively in space/time, they only allow one to engage ideas that can be expressed in such a linear format. The process of "projecting" experience into a philosophical proposition (or any sentence for that matter), guarantees that relations that may have been in any mode (acting, containing, and so on) will be treated as object relations, if they are "effable" at all. In our present culture, discursive forms have come to be identified with knowledge -- the knowable has been defined as the discursively sayable and all else is labeled feeling. To codify this linear systematicity, Langer lays out three "salient characteristics of true language, or discourse." They are:

1. Vocabulary & Syntax - symbols with fixed meanings (denotative consensus), & rules for construction of composite symbols (new meaning)

2. Dictionary - possible to define symbols in terms of other symbols

3. Translatability - multiple words with same meaning (1957 94)

In contrast, presentational forms are characterized by non-discursive symbols -- symbols that lack denotation and defy translation. Instead of linear exposition, a composite non-discursive symbol is placed before us, or presented. Even though we can generalize about nonverbal art-objects, this only happens in the linguistic mode, with words. With presentational form, the component symbols are understood as they relate to one another, a gestalt composed of both the parts and the whole.

At this point, the key question becomes "In what sense are these presentational symbols meaningful if they do not denote?" A discussion of presentational form in music, architecture, and painting can help to detail how media express meaning.

Meaning in Three Arts: Music, Architecture, Painting

Taking music first, Langer approaches the problem of artistic communication by noting that what distinguishes a "work of art" from a mere "artifact" is significant form -- its manner of presentation holds significance, or meaning, for many people and it is therefore considered art. As has been noted, presentational significance is distinctly a-denotative. Because music is the most non-referential of all the arts, it is a paradigm mode of presentational symbolizing that allows access to "purely artistic meaning." Just as discursive forms can express rational knowledge, presentational forms are capable of expressing affective ideas. That is, feeling does not belong to the inexpressible or unknowable because it enters the realm of articulate knowledge through exposition in non-discursive symbolic forms like music:

Music is not self-expression, but formulation and representation of emotions, moods, mental tensions and resolution - a 'logical picture' of sentient , responsive life, a source of insight, not a plea for sympathy. Feelings revealed in music are not the passion, love, or longing of such and such an individual, inviting us to put ourselves in that individuals place, but are presented directly to our understanding, that we may grasp, realize, comprehend these feelings, without pretending to have them or imputing them to anyone else. (222)

Formulation and representation is an apt description of all symbol use, and music has a close relationship with emotion in particular because it is formally analogous to the dynamic and transient play of affective life and even thought itself. The significance of music rests on the combination of two qualities; its explication of abstract emotive patterns (Gestalten) and the "sensuous value of tone," but this meaning is not completed or fixed to the same extent as discursive symbols:

For music at its highest, though clearly a symbolic form, is an unconsummated symbol. Articulation is its life, but not assertion; expressiveness, not expression. The actual function of meaning, which calls for permanent contents, is not fulfilled; for the assignment of one rather than another possible meaning to each form is never explicitly made. Therefore, music is significant form - implicit but not conventionally fixed (240-1).

This is precisely the point at which we can point to the fundamental irrelevance of the negative for presentational forms. Because music articulates rather than asserts, it is always a creation and never a negation. Absolute music presents us with an aural experience, a sonorous development over time, that expresses ideas about human life and emotion rather than propositions about reality or prescriptions for behavior.

Candidates for the negative in absolute music might include silence and dissonance. Neither approach the “thou shalt nots” of Burkean logology. Silences, or rests, are an essential part of music; pauses and timing are its breath and life. For instance, in Mozart’s Abduction from the Seraglio, the “Alla Turka Rondo” generates its impact by delaying expectations and then abruptly completing the rhythms established early in the piece. It uses silence to build up anticipation, not to negate.

The same principle of non-negation applies to dissonance in harmony. Not all human experiences proceed in smoothly modulated progressions, many times our emotions clash and music that is relevant to people who feel these emotions (such as youth or the avant-garde) can articulate these feelings by clashing with traditional harmony. In western music, one of the best-known harmonic clashes is the diminished fifth — this interval does not negate anything else, it is a clash on its own terms, with its flat V beating against its tonic. It sounds so “wrong” that, during the medieval period, it acquired the nickname “diabolus in musica” and was banned from church composition by Guido of Arezzo. It was later classified, along with the minor 2nd, as a Perfect Discord, and even today is still “associated with evil” (Arnold 1848-9). The important feature to note here is that the diminished fifth is a sound, an aural/temporal vibration that is unmistakably present — it is fundamentally here, in the air, in the room with you. It does not cancel anything out, it clashes with itself and broadcasts its troubled energy for all to hear.

Perfect 5th Traditional Consonance

Diminished 5th Traditional Dissonance

Diminished 5th in context: Black Sabbath Reunion – Epic E2K 69115

A similar point can be made with Architecture, the most material of the arts. Where music articulates temporal rhythms, architecture creates spatial rhythms. In this sense, both arts are concerned with order, and the relation between parts and whole depends upon harmonious integration rather than negation. In his classic study of architectural form and meaning, Venturi discusses how complex symbols necessarily integrate diverse forms to convey meaning. Instead of the either/or model of linguistic negation, the simultaneous inclusion/exclusion dynamic of architectural elements (walls, doors, and so on) requires a both/and approach to structural meaning. He goes on to point to the bond between the aesthetic and the ethical by distinguishing invalid forms of order (absolute and one sided, only excluding or only including) from valid orders (that balance the oppositions inherent in building). “A valid order accommodates the circumstantial contradictions of a complex reality. It accommodates as well as imposes. It thereby admits of “control and spontaneity,” “correctness and ease” — improvisation within the whole. It tolerates qualifications and compromise.” (41) The parallel to ethics and politics is immediately apparent. Architectural order that does not acknowledge and embrace both the one and the many sets itself up as a tyrannical structure fundamentally irrelevant to anyone that does not share its basic assumptions. Great art, great architecture, transcends its association with a particular time, place, and purpose to depict the universal.

An excellent example of architectural significance achieved through formal balance of the inside/outside opposition can be found in the Gothic cathedral’s approach to walls and windows:

The stained-glass windows of the Gothic replace the brightly colored walls of Romanesque architecture; they are structurally and aesthetically not openings in the wall to admit light, but transparent walls. As Gothic verticalism seems to reverse the movement of gravity, so, by a similar aesthetic paradox, the stained-glass window seemingly denies the impenetrable nature of matter, receiving visual existence through an energy that transcends it. . . . In this decisive aspect, then, the Gothic may be described as diaphanous architecture. (von Simson 3-4)

St. Etienne, Bourges France

Begun mid 1190s

Photo by Jeffrey Howe

Digital Archive of Architecture – Boston College

http://infoeagle.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/fnart/arch/gothic/bourges/bourges02.jpg

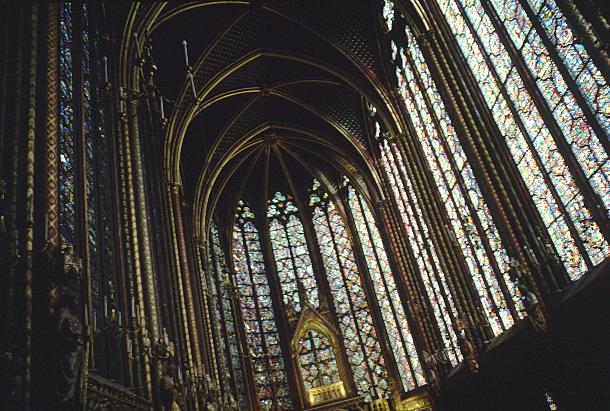

The “seeming denial” in northern Gothic architecture is just that, an apparent denial best seen as a transcendent fusing of oppositions. In combining matter and light, the Gothic wall becomes something more than either of the two alone, a luminous zone that demonstrates the fundamental presence of God in all things.

Ste. Chapelle, Paris France

1243-48

Photo by Jeffrey Howe

Digital Archive of Architecture – Boston College

http://infoeagle.bc.edu/bc_org/avp/cas/fnart/arch/gothic/chapell2.jpg

As human creations, even material structures like walls and windows are ultimately more symbolic than real; Langer says that they create “virtual space,” a realm wherein a culture enacts itself:

Symbolic expression is something miles removed from provident planning or good arrangement. It does not suggest things to do, but embodies the feeling, the rhythm, the passion or sobriety, frivolity or fear with which any things at all are done. That is the image of life which is created in buildings; it is the visual semblance of an “ethnic domain,” the symbol of humanity to be found in the strength and interplay of forms. (1953 99)

As monumental religious buildings, the cathedrals were designed with an explicit and direct rhetorical purpose based on the Gothic theory of anagoge. The “domain” created is one that presents the parishoner with an environment that enables him to discover God in the walls themselves.

In sum, unlike language, architecture is not founded on negation. Every element that excludes must also, at the same time, include a given area. In the same way, music is not founded on difference and the negative. Instead, it works by ordering tone and silence, activity and rest, tension and release. Great architecture accepts and celebrates the internal/external dynamic; great music moves with human grace. With our final art, Painting, we can see how presentational form works in purely visual space.

In his book on Basic Design: the dynamics of visual form, Maurice de Sausmarez approaches the visual arts through gestalt psychology and the laws of visual perception. He tells us that:

sight is more than the mere optical stimulation of the retina by haphazard light rays, which the mind concurrently organizes into spatial units. It is virtually impossible to perceive units isolated from and unaffected by the context in which they appear. Relationship is inescapable and this makes the act of looking a dynamic experience. (16)

Because of this necessary interdependence between figure and ground, painting, the art designed for vision alone, must present both a focal point and a context. Each is fully implicated by the other through their joint structuration of the picture plane — there is no sense in which the one excludes or negates the other. de Sausmarez makes this point clear: “We are forced to recognize the fact that in the field of vision nothing is negative. The space round and in the image is as positive as the image itself.” (43) In this simple design, the black and white portions are completely dependent upon one another.

. . . on White on Black on . . .

Jon Radwan

2000

One of the artistic movements that takes best advantage of painting’s figure/ground dynamic is Cubism. In reaction to the renaissance tradition of realistic representation achieved through foreshortening and precise development of singular perspective, Picasso and the cubists bring the entire canvas to life with multiple perspectives that activate pictorial space by giving it a varying relationship to each of the figures. Here is Golding’s description of Braque’s Le Port:

The treatment of the sky and of the areas between the various landscape objects, the boats, lighthouses and breakwaters in terms of the same facets or pictorial units into which the objects themselves are dissolved, has the effect of making space seem as real, as material, one might almost say as ‘pictorial’ as the solid objects themselves. The whole picture surface is brought to life by the interaction of the angular, shaded planes. Some of these planes seem to recede away from the eye into shallow depth, but this sensation is always counteracted by a succeeding passage that will lead the eye forward again up on to the picture plane. (79-80)

Harbor in Normandy

Georges Braque

Scan by Mark Harden

http://www.artchive.com

Painting, architecture, and music each present us with symbolic formulations of experience — they communicate and express our uniquely human ideas about ways to order vision, space, and time. Meaning in these arts does not depend upon differences between signifiers or the hortatory negative. Instead, their meaning arises from the ways in which they articulate a spatio-temporal presence, an aesthetic event designed to engage our fundamentally human ability to formulate experience — as Johnstone says, in mediating or symbolizing, we “hold” experience at a distance so that we can learn about and appreciate different ways to interpret human experience.

Conclusion

The linguistic bias of most rhetorical theory prevents us from understanding how non-discursive communication generates meaning. To underscore the difference between Discursive and Presentational symbols, this essay has shown that the negative fails to explain meaning in particular forms of art. In this sense, we have introduced a rhetoric of presentational symbolism in three media: music articulates ideas about action through tone and silence, architecture creates cultural space by negotiating the inside/outside dynamic, and painting orders vision by depicting figure/ground relationships. All of these art-forms are fundamentally present – they do not rely upon systemic negation or abstraction, they are primarily themselves and their meaning arises from the integration of their parts into significant wholes.

When symbolizing is no longer equated with languaging, new questions about the scope and center of Rhetoric present themselves. Discourse always has presentational dimensions, such as layout in writing or paralanguage in speech, but the reverse is not true. Presentational forms do not require discursive dimensions to be meaningful, and this indicates that the presentational symbol is logically prior to the discursive. To fully understand social influence, we must leave logology and look for the basis of meaning in other, more primal, conceptions of the symbol. To displace The Word as archetypal human medium, consider The Gesture. Generally, gestural theories maintain that humans communicated before the development of verbal language, and that the spoken word is essentially a refined form of expressive gesture.[8] R.G. Collingwood outlines a strong theory of communication as gesture by denying verbal expressions their exclusive right to the term “language”:

Bodily actions expressing certain emotions, in so far as they come under our control and are conceived by us, in our awareness of controlling them, as our way of expressing these emotions, are language. . . In this wide sense, language is simply bodily expression of emotion, dominated by thought in its primitive form as consciousness. (235)

Here, discourse is merely one form of bodily action among many. When Collingwood refers to “art as language” he means art as a controlled articulation, a physical expression of ideas and their accompanying psycho-emotional “charges.” Because we are physical beings, there is an inescapable motor side to all imaginative experience, and this is ultimately what we encounter as art. “I mean that each one of us, whenever he expresses himself, is doing so with his whole body, and is thus talking in this ‘original language’ of bodily gesture.” It is in this sense that dance becomes a root-metaphor for all expression; “the dance is the mother of all languages.” (244-6) Even non-performative artworks like paintings and architecture always refer back to the original “dance” of creative actions that began their life as a material focal point for experience. If we extend this powerful image, social life can be seen as a kind of communal dancing, with each individual granting pattern to a life by choosing (agreeing?) to perform particular dances, with particular partners, at particular halls.[9]

In today’s mediated world, rhetorical theories that do not account for presentational form cannot enable us to effectively interpret and participate in social exchange. Collingwood’s placement of dance as archetypal medium is miles removed from Logology, and it represents a direction that rhetorical theory must take if it is to account for non-discursive symbolic forms. By exploring the interaction between discursive and presentational symbols, we can develop a vocabulary that describes mediated rhetoric without relying upon the linguistic assumptions built into the rhetorical tradition.

Back to Top

Home | Current

Issue | Archives

| Editorial Information

| Search | Interact