|

|

|

|

![]()

Volume 4,

Issue 1,

Fall 2000

Altar

Rhetoric and Online Performance: Scientology, Ethos, and the World Wide

Web

Todd

S. Frobish

| Abstract The intensity and speed with which the online environment has altered society pushes the limits of the modernist belief that religions should adjust to cultural changes. This raises a number of problems for religions moving online, such as recruiting and sustaining traditional followers while adapting to and targeting the growing online population. In this essay, I pose two primary questions: (1) How can a religion that has credibility problems offline hope to create a credible identity on the Word Wide Web (WWW)? and (2) What Web technologies might act as part of an ethical strategy? More specifically, I investigate how Scientology responds to its own credibility issues by constructing an image of goodwill built upon a communal portrait of peace and well-being. A textual examination of Scientology's website reveals that religious organizations can use the WWW to establish personas in ways that are much more effective online than offline. |

Assistant

Professor Speech Communication Studies Iona College 12 President St. New Rochelle, NY 10801 tfrobish@iona.edu http://www.iona.edu/faculty/tfrobish |

Introduction

The Internet is fertile ground for religious groups that want to attract new followers. The World Wide Web (WWW) has become a sanctuary for groups seeking to renew themselves in light of the growing online population. A recent count of religious websites on AltaVista, an online search engine, revealed slightly more than 200,000 religious sites. Yahoo, a website directory, lists more than 1200 religious categories, from African-Religions to Zoroastrianism. In the category for Christianity, Yahoo includes more than 9300 websites. Consider that even the best search engine accounts for a trivial number of active websites, and one can begin to sense the immensity of the environment.1 But as this playing field grows, religions, factions, and cults will be in competition and questions of religious credibility will inevitably arise.

Scientology is one such religion that has moved online. Scientology is unique, however, since its move online resulted not because of a need to reach new followers, but to respond to its offline credibility problems. Further, Scientology is a self-proclaimed religion that constantly seeks legitimacy from the government, the media, and its critics. If Scientology is able to succeed online—to establish a credible identity by employing Web technologies—then it seems reasonable to assume that the Web has potential for all religions. Therefore, Scientology provides a key case study in the examination of religions online. In the first section of the essay, I look at the ways in which the Internet provides opportunities for religions—groups we assume ought to embody the highest level of virtue. Second, I explore what we might expect of a religion that has moved online by examining past rhetorical thought and what it has to say about religious character. Third, I discuss how the Web environment complicates the character-building process by creating special obstacles to religious groups. Fourth, I explore the historical background of Scientology as a religion with tremendous credibility problems. Fifth, I evaluate Scientology's online persuasive efforts. Finally, I discuss the study's implications and limitations.

"Religion" is a complex and difficult abstraction. Jennifer Cobb, author of Cybergrace, contends that "theology seeks to articulate that which is fundamentally inarticulable. It is an effort to bring to light issues of soul, spirit, and faith" (14). We could define religion in the broadest sense as

(1) a system of symbols which acts to (2) establish powerful, pervasive, and long-lasting moods and motivations in men [and women] by (3) formulating conceptions of a general order of existence and (4) clothing these conceptions with such an aura of factuality that (5) the moods and motivations seem uniquely realistic (Geertz 90).

Although religion has always been a source of controversy, the online environment has spawned an entirely new era of spiritual questions. Is God on the Internet? Does the visual capability of the Web offer a new hermeneutic for interpreting the Bible or other religious writings? How does one give an online sermon or prayer? Pope John Paul II, for example, has been netcasting his religious sermons in order to reach a larger audience since August, 1998, by using RealAudio software (Brandis 1998). So what does it mean to pray with others virtually? Can one find enlightenment and peace online? Specific to this investigation, how can a religious group establish a traditional form of credibility through a non-traditional medium like the World Wide Web?

Although some may wish to avoid the growing confusion, others are ecstatic. Cobb writes that "cyberspace has vast, untapped potential as a creative medium infused with divine presence" (15). She further argues:

What is unique about the immersive experience in cyberspace is that it is fundamentally interactive. In cyberspace we have agency . . . we can interact with plain text in cyberspace in a way that opens us to new levels of immersive experience (10).Indeed, the possibilities exist for virtual tours of the Bible, conversations with dead and living prophets, or a walking journey with Jesus. With the level of interactivity possible online, one may feel closer to God in a way that is not possible by hearing sermons in Church or reading scripture in print.

While it seems that there are too many religions to examine, these religions are increasingly more accessible to the computer literate public. In a matter of seconds, a user may travel from the Vatican's website to the Satanic Network, from speaking to a Buddhist monk to having words with a cult fanatic. Using the Internet to broaden our experiences may be a positive trend, but it is also very easy to deceive and to be deceived on the Internet. This raises problems for religions moving online that wish to establish credibility and these problems must be met in response by those who construct their websites. Aristotle noted that the first step toward establishing trust is creating the perception of practical intelligence, moral virtue, and goodwill toward the community. Mitra posits that because of the increasing influence of computer-mediated communication (CMC) in our lives, the WWW and its designers must play a role "in the production of a virtually connected community of people" (159). Cobb claims that "it is only in the context of communal reflection that the sacred dimension of cyberspace will truly flourish" (237). If Mitra and Cobb are correct, the appearance of a positive religious ethos based upon the perception of communal goodwill is critical to the success of any religion. A look at past rhetorical thought with regard to religious ethos may lend perspective.

A long history of debate over ethos is evident in the rhetorical tradition. The term has been characterized by a tension among what qualities we ought praise and condemn. Aristotle included practical intelligence, moral virtue, and goodwill, in his conception of ethos. The Romans later added concepts such as modesty, temperance, honor, and courage. In the centuries following, the construct has grown exponentially more complex, including more modern concepts such as dynamism and charisma. Ethos is, at its core, a perception—an illusion wrought by a rhetor in selecting appropriate and sometimes inappropriate words, artifacts, and actions, in order to gain the trust of the other. To this extent, Aristotle asserted that "this should result from the speech, not from a previous opinion that the speaker is a certain kind of person" (Kennedy 38).

Aristotle established his idea of credibility sans reputation so that those without a known reputation might have an equal chance to defend themselves in the court system. However, it seems overly facile to assume that reputation was not instrumental in persuading an audience. Indeed, in the classical agora, reputation—what was commonly known about a person's prior actions and family history—was a form of initial ethos.2 Audience members could verify these assertions if the community were small enough. On the other hand, the online audience is dramatically larger. And since the Web environment was created without traditional gatekeeping controls such as editorial boards, there is little way of verifying the words of another, especially if there is no feedback mechanism such as an email link or a telephone number. Moreover, it is difficult to assess the recency of information since there is often no way to verify how long the information has been online. Even if there is a last-updated date on the site, verfying the date's accuracy is difficult. It seems reasonable, then, that establishing trust between an online group and its users may be more difficult than it might be offline, in a face-to-face situation. Despite these obstacles, religions that wish to go online must shape their identity by appealing to what might be called a traditional view of religious character while simultaneously filtering those traditional appeals through the new environment and it technologies.

Eighteenth century epistemologist and minister George Campbell spoke to what might be called traditional religious ethos. Campbell argued that the preacher-orator had the hardest job convincing an audience, since the audience received its moral guidance from the orator. The orator must exist without flaw. To facilitate this image, the orator had to "excite some desire or passion in the hearers" and then "satisfy their judgment that there is a connexion between the action to which he would persuade them, and the gratification of the desire or passion which he excites." Religious ethos is one of authority and must be established by embracing moderation, candor, and benevolence. "The preacher," Campbell noted, "is the minister of grace, the herald of divine mercy to ignorant, sinful, and erring men [and women] and also the man [or woman] of justice and wrath." The preacher-orator, therefore, must exemplify the pinnacle of morality and show concern for the community in order to persuade its audience.

Any religious group may construct such a communal ethos through actualization, projection, and association. First, it can actualize ethos demonstratively or, in other words, perform it for the audience. It is an ethos of linguistic action. When speakers point to the charitable deeds that they have done in the past, it is an attempt to alter the perception of their reputations by actualizing ethos. The strategy is typical of much discourse, not just religious communication, but also in forensic and deliberative rhetoric. Lawyers, for example, construct witnesses' and defendants' credibility by their listing accomplishments and deeds, or, simply stated, prior action. If the speaker is unable to talk about the positive deeds that he or she has accomplished, his or her ethos is weakened. Similarly, religious leaders must demonstrate to the audience moral virtue and a concern for the community by talking about past actions that have helped the welfare of the larger community.

Projection is a second vehicle through which ethos may be created. If one looks at the speaker's discursive choices, the clothes that the individual wears, the speaker's mannerisms, for instance, one has a certain view of that person's character. These attributes constitute part of the performance and are stylistic choices that affect the speaker's appearance of authority, virtue, and so on. Projected ethos is not created through words about prior action, but is fashioned through immediate verbal and nonverbal cues. Black gives us a hint:

When, for example, the judge is robed, the garment neutralizes the individual appearance; it depersonalizes the wearer. The person is concealed. Similarly, the white sheet of the Klansman obscures an angry redneck, and proposes instead an embodiment of social interests and moral emotions. It is, indeed, not the person but the role that is elevated and the subordination of the person to the costume assists this process. (136)Rhetors who attempt to establish credibility by showcasing the persons with whom they transact and relate are projecting a third type of ethos—one created through association. This formation of ethos is key for online groups. If they are be able to demonstrate that they retain a "community" of followers who believe or trust in their religious belief system, it seems reasonable that they may be more successful in attracting outsiders. Depending upon to whom and how successful the connection is made, a religious group may be perceived credible beyond that which may have been possible by listing past deeds or its historical record. Moreover, on the Web, links from an organization's website to another can figuratively and literally link one group's ethos to a community of others, which may help facilitate building this form of credibility.

Several scholars help us understand how an associative ethos might work. Hart et al. contend that one method for improving one's perception of competency, an element of ethos, is to associate oneself with other high-credibility sources. Osborn and Osborn suggest that in basic public speaking, citing or using experts to strengthen one's speech or position "allows you to borrow ethos from those who have earned it through their distinguished and widely recognized work" (155). Logue and Miller state that "rhetorical statuses arise when communicators position themselves to each other, as each takes account of salient qualities of self and other" (20). These authors further argue that "each person at any time has many rhetorical statuses, depending upon the extent of that person's communicative relationships" (21). The types of connections made to other people or other communities can substantially affect the degree of perceived credibility.

Computer-mediated communication (CMC) has altered the means by which many religions teach and inspire.3 O'Leary and Brasher claim that as traditional religions enter or experience CMC, they radically transform, a metamorphosis that has "parallels in the historical evolution of Christianity as it resisted, adopted, and adapted the concepts and methods of classical rhetoric" (234). In light of our new media revolution, religions may constantly seek to renew their credibility by taking advantage of modern technological changes. Indeed, the belief that religions ought to conform to cultural changes is well-documented as a central tenet in modern Protestant theology and was theorized by its father, Friedrich Schleiermacher: "Culture and religion are related . . . not as parent and child, nor as antagonists, but as joint heirs and products of the religious sentiment that constitutes human apprehension to God" (Hutchinson 5-6).

What are some of these cultural changes? First, the audience is constantly changing as new users go online. Some estimates approximate that more than 1 billion webpages exist and are increasing rapidly (Nua). According to one Internet research group, the Nua institute, some 305 million people are online in the world and a third of these online users (123 million) live in the United States.4 Yet, these numbers are already dated and this changing audience makes targeting a particular group difficult for online religious institutions. Furthermore, O'Leary and Brasher argue that CMC has altered the traditional space where individuals used to pray and meditate, turning it into an electronic public forum where these same people now "meet to expose their religious and philosophical beliefs to the scrutiny of nonbelievers or exponents of other faiths, and to engage in debate and discussion with others" (250). These online religious spheres offer challenges to those who would ordinarily find comfort in their place of worship. O'Leary and Brasher note that "Net discourse has the potential to level old hierarchies and status or to allow people to move more freely among them, enabling (for example) people without theological training to engage in dialogues with clergy or university professors" (252). Instead of exposing their religious and philosophical beliefs to the scrunity of nonbelievers, as O'Leary and Brasher suggest, religious groups may also use the Internet to address the criticism of skeptics or to recruit new members who will help support the mission of the religion.

Discovering new ways of constructing and enhancing one's ethos online may be necessary in the face of these changes and opportunities. The ability to link oneself to another is the very essence of hypertext and may be the key to constituting religious ethos. Without this utility, hypertext would be nothing more than reading a book or magazine; it allows us to construct "vast new publics connected to each other not by geography but by technological links and shared interests" (O'Leary and Brasher, 246). Within these publics, online religious groups must reconstitute their ethos in a way such that it embodies the unique tools of the medium or, as Aristotle would say, makes use of the available means of persuasion. This would suggest, then, that to construct an associative ethos online, one must take advantage of the hypertextual medium and the ability to link one's site to another. Taking a closer look at a current religion online and whether or not it has embraced the Web in this fashion, might help us understand the current status of the Web as a religious medium.

The Church of Scientology is among the many religious groups that have ventured onto the Web in search of members. To be successful, religious organizations must embrace the online environment as a vehicle for communication while appealing to our traditional views of religious character. Scientology provides a useful case study for online religious ethos because it has encountered many obstacles toward creating a credible identity offline, and may embrace the Web and all of its technologies with a fervor not seen elsewhere. The following is a brief review of Scientology's history of credibility problems and why Scientology has employed the Web as its central medium. This review will get us closer toward understanding Scientology's ethos-building strategies and, more generally, the potential of the Web as a persuasive, religious medium.

Scientology: A Brief History

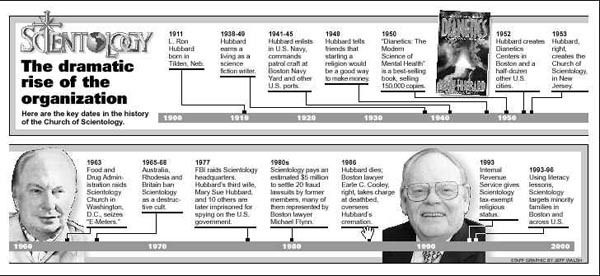

Timeline from: The

Boston Herald

A 1988 The New York Times article demonstrates the importance of image for Scientology. Frantz's article, "Scientology's Star Roster Enhances Image," centers on Scientology's strategies for legitimacy. Frantz notes that the Church gave its its "human rights" award to John Travolta, and observes that "more than any other church that has begun on the religious fringe, The Church of Scientology has cultivated a potent roster of celebrity members" in its "struggle to win acceptance as a mainstream religion" (A1). Its "use of celebrities," Frantz notes, "is part of a calculated, three-decade effort" (A1). Scientology may not yet be accepted as a mainstream religion, but its name is certainly in the news. Indeed, Scientology is controversial on an international level and it is within this context that we will be better able to understand its purposes online.

Born in 1911, Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard began what is now one of the most controversial religions in the world. After earning his living as a science fiction writer following college, Hubbard traveled to the West Indies to study mineralogy, yet unwittingly received an education about other cultures and their ways of living. That trip gave Hubbard the necessary insight to write his now infamous self-help book, Dianetics: The Modern Science of Mental Health, the foundation of Scientology's theology and immediate bestseller of 150,000 copies in its first year alone. He launched Scientology in 1952 and in 1955 he opened the Founding Church of Washington, DC. According to the foundation's website, Hubbard's legacy today includes more than "2,000 churches, missions and groups worldwide. It includes solutions to every social problem: crime, racism, drug abuse and illiteracy. More fundamentally, the singular technology he developed provides for the complete rehabilitation of human dignity, ability and spiritual potential."

A brief explanation of Scientology's basic tenets is available on its website. Eschewing the concepts of original sin and faith, Scientology believes that humans are basically good and that, since followers will discover on their own the pragmatic uses of the religion, faith is unnecessary. The What is Scientology? website reports:

Scientology is a religion which recognizes that man is basically good and offers toold anyone can use to become happier and more able as a person and to improve conditions in life for himself and others, and to gain a profound understanding of the Supreme Being and his relationship to the Divine.Scientology's three fundamental truths include: (1) Humans are immortal spiritual beings, (2) Our experience extends well beyond a single lifetime, and (3) Our capabilities are unlimited, even if not presently realized. On its Why is Scientology a Religion page, Scientology claims that it:

meets all three criteria generally used by religious scholars when examining religions: (1) a belief in some Ultimate Reality, such as the Supreme Being or eternal truth that transcends the here and now of the secular world; (2) religious practices directed toward understanding, attaining or communication with this Ultimate Reality, and (3) a community of believers who join together in pursuing the Ultimate Reality.While enlightening for some, Scientology has its critics. In March, 1998, Boston Herald reporter Joseph Mallia wrote a five-day series of articles lambasting Hubbard's dubious achievements, the religion's financial misdealings, its unproven and possibly dangerous anti-drug program, and its criminal handling of skeptics. Among the more critical remarks, Mallia reported: (1) the cost of Scientology's training is said to total $376,000 to complete and (2) many of Scientology's ex-followers "say they were manipulated, abused, or held captive when they tried to leave the church."

Today, this very public war between Scientologists and critics is being fought on the Web. As one critic noted, using the Web to reveal Scientology's less than honorable conduct is the key to destroying Scientology's power and would likely "tear apart the church's reclusive leadership." (Mallia). Mallia claims that in response to these charges of misconduct, Scientology "unveiled a new 30,000-screen World Wide Web site, aimed mainly at attracting new members and selling its costly programs." How exactly has Scientology shaped its identity in defense of these credibility issues while filtering its messages through the online medium? Through a close textual reading, I will assess how Scientology's website answers questions of religious character through the use of the WWW.

Many scholars have preferred textual criticism for the analysis of religious documents.5 TC: A Journal of Biblical Textual Criticism, published by University of Michigan Press, is an electronic journal dedicated solely to the interpretation of Jewish and Christian bibical texts. A website inspired by The Encyclopedia of New Testament Textual Criticism claims that religious textual criticism is about "working with the materials available, to reconstruct the original text of an ancient document with as much accuracy as possible." However, this form of textual criticism is concerned with a different set of questions than what I propose here. Rhetorical scholars search not to find the correct interpretation of a document or object, but possible symbolic meanings. This style of textual criticism, as Leff argues, "is to divert attention away from theoretical constructions and to focus on the rhetorical action embodied in particular discourses." (164). Religion has been of scholarly interest to many rhetoricians, but few, if any, have looked at religious websites. While I base this examination in a classical understanding of "character," it is my goal as a textual critic to investigate Scientology's rhetorical strategies by locating meaningful rhetorical patterns and situating them within its discursive context. The following reading of Scientology's main website attempts to follow such a perspective.

Scientology's website takes full advantage of Web technologies in order to build a credible identity capable of attracting and sustaining visitors. The site is a massive collection of images, links, and textual information that might take even veteran users weeks to explore. One does not have to venture far, however, to see that the site is carefully designed to take advantage of the visual and interactive capabilities of the medium. Upon visiting Scientology's website, one finds an array of computer-designed, brightly-colored text and images. Furthermore, its main page allows the user to email for more information, take a virtual tour of Scientology's organizational structure, listen to Hubbard via RealAudio, and experiment with Scientology's online personality tests, to name only a few. It seems obvious that Scientology wishes to keep its users entertained or otherwise immersed with its sheer volume of online activities. It also seems apparent that, since the visitor can choose among four language options including French, Spanish, Italian, and German, Scientology is not targeting just U.S. visitors, but a European audience too. Despite these gimmicks, however, Scientology must establish an identity capable of building trust between it and online visitors. Scientology attempts to promote a particular religious and political persona by linking itself to common societal images of benevolence, authority, and legitimacy. More specifically, Scientology utilizes the Web to actualize, project, and to create through association, a credible religious ethos.

|

Scientology's website designers attempt to create a benevolent, community-oriented image, as the graphics included here suggest. As soon as the first page appears, one can find the word "free" repeated in four distinct places: "The Scientology Workshop," an "Orientation Film," a "Scientology Information Pack," and a "Personality Test ON-LINE." Scientology's repetition of the word "free" projects an image of charity or of altruism. On the "Related Sites" page, Scientology states that its programs service the community. Scientology keys into ethos-related terms such as ethics, social betterment, public benefit, human rights, rehabilitation, education, trust, honesty, moral values, and criminon (or without crime), throughout a discussion of its reputation and future agenda. Certainly, these ideographs portray the church in a positive light and help to build admiration for its social agenda. |

|

Several of Scientology's main links begin to show a different side to its image. Each of these are connections to sites plugging Scientology founder L. Ron Hubbard's bestselling books. In fact, one of the central links from the organization's main page is to "The Scientology and Dianetics Online Bookstore," where users can "visit the most comprehensive collection of L. Ron Hubbard works and biographical information on the Internet." While these links do suggest some sense of community, offering access to a common body of knowledge and to the Church's historical record, it appears financially motivated, congruent with its critics' allegations. It may be another way in which visitors are asked to "buy into" the Scientology's value-system. |

Aspiring to address its (lack of) credibility issues, Scientology attempts to answer visitors' concerns with a page called "Scientology Questions & Answers ." The text of the link states: "The President of the Church of Scientology International Answers Your Questions." These are not just any questions that the President will answer, however, but are "The most frequently—and candidly—asked questions about Scientology taken up one-by-one." After following the link, however, one finds a different sentiment. Instead of addressing questions, the page now refers to these issues by stating that this section is about "Misconceptions." Why the discrepancy between the two descriptions?

| The two are seemingly bi-polar in nature. The first indicates an up-front and open discussion concerning questions from inquiring individuals. The neutral tone of the phrase, "Answers Your Questions," is personalized and seems intended to draw interested parties. And since the answers come from an authority, the President of the Church, rather than a common member, they appear credible. However, the text of the second link, phrased rather curiously, queries "What Misconceptions are there . . . ?" The tone here is not neutral and suggests wrong-headedness, perhaps on the part of its skeptics. This phrase is leading, implying that any critique of Scientology must be wrong. Furthermore, it seems reasonable that since visitors might not go to a page labeled "Misconceptions," Scientology judiciously presents the page as FAQ. |

|

The battle with the Internal Revenue Service was finally and favorably resolved on October 1, 1993. On that day, the IRS issued letters recognizing the Church of Scientology International and its related churches and organizations—all 150 of them—as tax-exempt under section 501(c)(3) of the Internal Revenue Code.Apparently, Scientology felt a need to prove to its non-members its religious legitimacy and this tax-exempt status offers it that chance. Scientology answers the second question, "Why has the Church of Scientology been at odds with the U.S. government in years past?" by stating that "the reason for the attacks against Scientology is basically very simple. Its genesis was not wrongdoing by the Church, but the perceived encroachment on turf claimed by the American medical/psychiatric community." The "attacks against Scientology" and "perceived encroachment on turf" are battle metaphors alluding to the same sort of issue in the first question—financial. Indeed, the war metaphor seems to permeate throughout the entire site, creating a sort of us/them dichotomy.

Although these answers may help us to understand Scientology's religious and political positions, there are incongruencies between the organization's online persona and linguistic allusions. Underlying these incongruencies are attempts by the Church to address its offline credibility problems. Indeed, we might say that the entire website is designed strategically to counter its critics' allegations over what they might say is a questionable image of benevolence, authority, and legitimacy. The following section looks more closely at these strategies by examining the way in which the Scientology website actualizes, projects, and creates through association a credible religious identity.

The Church of Scientology presents an actualized ethos characterized by a long, successful history of helping others achieve their spiritual, physical, and mental best. The Church tells its readers, on the site's first question-and-answer page, that "the ultimate goal of Scientology is true spiritual enlightenment and freedom for the individual." Later on the page, the Church states that it has always pursued an agenda created "for improvement of their communities and society." The Church claims that the Hubbard College of Administration is "based 100% on basic laws which have been tested time and again and proven to be completely workable." Moreover, the "important moral lessons contained in Mr. Hubbard's The Way to Happiness booklet," are there to help " restore trust and honesty to our society." The Church, the "world's fastest growing religion," is making "the entire business community a better place in which to work." The Church "solves education" by offering "solutions to effective learning and education using the Study and Learning Technology developed by L. Ron Hubbard." The Church helps prevent crime in society by "applying the rehabilitation methods discovered and developed by L. Ron Hubbard." The Church casts its "Applied Religious Philosophy" as a panacea for the World's afflictions. Scientology's stated reputation is, therefore, an important part of its identity.

The Church of Scientology presents a credible, projected ethos characterized by professionalism and authority. Its use of style and arrangement or the context in which its words are cast is critical on the Web. The formatting of the page—the clothes of the discourse—should project an image of professionalism that we would expect from a religious institution. Throughout its site, Scientology takes great pains to make its site look and feel pleasant. Its images are eloquent, full of vivid colors, and are appropriately chosen for Web display. Indeed, the colors that emphasize the organization's main logo, background effects, and most of its imagery are carefully selected to represent an earth-centered philosophy.

|

|

The site's section arrangement is also strategic. There are five main sections on its first page:

- What's New

- Special Features

- What is Scientology?

- Bookstore

- Global Locator

| This order is important: Items appearing at the top of webpages usually suggest importance, whereas bottom material typically alludes to less vital content. The Church's free give-a-ways, for example, appear first on the screen before its more informative "question and answer" section. Its print-form books, furthermore, appear more important than reading its online "comprehensive guide to the Scientology religion." In fact, some of the site's features first-mentioned consist of a book for purchase entitled What is Scientology?, a link to "New Sites and Publications," and, though Hubbard died in 1986, there is another link to "Newly Published Books by L. Ron Hubbard." The website appears designed to attract visitors who are financially middle to upper class. Indeed, after clicking on the link to buy What is Scientology?, the site features the opinion of a middle-aged man: "When I found Scientology I learned how to help other people get along with others. All this has led me to a good, healthy, sane life." The subtext below does not give his name, only the title "Businessman." |  |

The Church's "Awards" page is also strategic, speaking to Scientology's motivations. Website awards have become so ubiquitous, that to a large degree they have lost their merit and meaning. Scientology lists seventeen website awards. These awards are not linked to any originating source, so the user is left to trust Scientology and the veracity and quality of the award committees. Beyond this, some of the awards are dubious. One boasts that Scientology's website ranks in the top five percent of the Web in terms of quality. With 8 million websites, that honor places Scientology within the first 400,000. Another awards Scientology the "Ravi Award," which includes the comment, "Congratulations! Your site has been selected by me, Ravi Sarin, as an elite site. I feel your site deserves to be on the list of Elite Web Sites." How large is this list and what are its qualifications? Just above this, Scientology highlights its "Will's Award for Excellence." Who is Will? Without any way of verifying the information, these awards seem meaningless. However, that the Church offers a link from its main page to website awards is germane to this study. For what other reason would website awards have on a religious group's website if not to project an image of legitimacy and authority? These are the clothes with which Scientology adorns itself—the dressing that it wears to address its problems, to influence our perceptions of its credibility.

In addition to maintaining a projected ethos, Scientology's website advances an associated ethos. An associative ethos is built upon the characteristics of others to which the rhetor can demonstrate connections. For instance, the Free Scientology Workshop offered on the main page boasts of its host: "Jenna Elfman of ABC's hit series 'Dharma & Greg.'" Also, "L. Ron Hubbard," the name of Scientology's founder, is cited four times on the main page and fifteen times on the "Related Sites" page. The "What Religious Scholars Say About The Scientology Religion" page cites expert testimony from some 60 scholars and religion experts:

The results so far include 60 studies by a roster of distinguished scholars. Each has analyzed Scientology from his [or her] own perspective, and in some cases, compared it to other religions. The common denominator of all the studies is that although its historical and philosophical roots go back 10,000 years, Scientology is thoroughly contemporary. The scholars agree that it is unique among religions, with its precise path to greater happiness and fulfillment for people from all walks of life.While the page mentions the names of people who confirm Scientology's claim to religion, those who oppose it are, not surprisingly, not mentioned. Those who would expect on a sub-page, "Those Who Oppose Scientology," to find narratives and explanations by critics, would be surprised to find nothing on the subject. This seems to support the notion that rhetors will connect to individuals they think will most likely influence an audience's perception of their credibility. Since, as research shows, an audience is apt to be more persuaded by a person (or institution) they believe to be credible than one who is not, it seems as if Scientology has chosen an appropriate persuasive strategy.

Scientology attempts to create the impression that it constitutes a community. Recalling Aristotle, positive ethos can be created when a speaker shows goodwill toward his or her audience. Groups, furthermore, that can create the perception that they speak for the benefit of the larger community will appear more trustworthy than those that do not.

Looking more closely at the type of community Scientology attempts to create on its website reveals another image. While I mentioned earlier that Scientology seems to target a financially endowed audience, Scientology has created facilities, labeled Celebrity Centres, that offer to the institution's more illustrious members private counseling and health services (Frantz A1). Frantz notes that, "Although the facilities are open to all Scientologists, internal church documents show that their primary purpose is to recruit celebrities and use the celebrities' prestige to help expand Scientology" (A1). By reaching out to celebrities, associating their names with the Church's, Scientology seems to want to gain legitimacy on a mass scale. It seems appropriate, then, that Scientology's home office is located on Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles, California.

Discussion

Scientology utilizes a variety of means to establish and enhance its credibility via the WWW. Scientology attempts to actualize, project, and create through association a particular form of religious ethos. The Church employs the unique characteristics of the medium—the ability to link to other sites, colorful images and animations, sound files of Hubbard's sermons, and well-formatted text—tto facilitate delivery of its messages and direct users' attention to the content the Church thinks most important. In its attempt to establish credibility, Scientology exploits these tools; it employs them not just to spread its faith, but to correct what it believes are "myths" and "misconceptions" about the Church.

Scientology's website is the burning bush of its apprehension over establishing credibility. Religions are made powerful by creating communities of believers. These communities will follow only as long as they trust the religious message, the senders of that message, and the overall goals of the church. To this extent, it seems appropriate that a church that is perceived untrustworthy will try many methods to rectify its image, to recreate an identity of benevolence, authority, and legitimacy. Specifically, by presenting these traditional components, the Church is attempting to establish a positive religious ethos. Scientology, however, tries at the expense of discretion. Its awards page, links to 15,000 followers, links to its worldwide member institutions, multiple free info-packs about the faith, and its many responses to popular "misconceptions," invite commentary about Scientology's motivations. The important point, however, is that Scientology is able, because of Web technologies, to employ all of these measures. How this identity is crafted in the Web environment, then, is the central issue.

While the specific focus on religious discourse is substantive, the larger locus of concern rests with how online groups can establish a traditional form of credibility by filtering its messages through new media. As observed with Scientology, religious groups can employ a large number of Web technologies to triangularly craft their ethos: ethos that is actualized, projected, and constructed through association. By utilizing awards, audio and video files, animation, professionally-designed images, text concerning goals and reputation, and expert testimony, rather than traditional broadcast media, Web designers have multiple tools to alter a religion's image by portraying the group as virtuous and benevolent. By making connections to "followers," "experts," and "reputable organizations," an online group can create the appearance of community. This seems to be a strategy easily embraced through the medium—a strategy available to those who feel a need to manipulate their image before a public audience.

Future Research and Limitations

Given this study's focus on a particular religious organization, there is not enough space to explore a number of worthwhile issues. Computer-mediated discourse is quickly growing in sophistication and size. Targeting issues of credibility alone leaves many unresolved issues. For example, future studies might address to what extent non-Christian religions have employed the Web, influence strategies used, and how these sites manage credibility issues? Inquiries into the religious use of the Internet for recruiting purposes, types of online worship, and how the websites perpetuate or expedite the accessibility of cults such as the "Heaven's Gate" group, are also important issues we must examine. Regardless of our particular questions, we should not forget how central establishing credibility is in persuasion and how important that role is on the WWW. The one safeguard users have online is their ability to assess the character of the message sender, whether that is an online religion, political group, or commercial enterprise. Investigating how these groups can employ Web technologies to create a credible identity will help us move a step closer toward increasing our understanding and safety.

Case studies, particularly those that examine websites, have several inherent limitations; there are a few I feel important enough to list here. The question of methodology is and might always be a weakness of Internet research. Because new Web technologies are developed daily, it is difficult to create a common topoi from which to examine and interpret website discourse. Furthermore, the possibility exists that everything on a website could be regarded as an ethical appeal, making the concept of ethos vacuous. A much more nuanced concept of ethos is necessary. Also, since, in this case, Scientology's website has 30,000 separate webpages, it was impossible to review every document. There may be some unreviewed page that may bring new light to Scientology's persuasive strategy. This is endemic to the entire WWW. Additionally, pages thought to be permanent may change the following day, making any sort of sustained inquiry impossible. These sorts of questions mean that the WWW may elicit much interest from scholars for years to come, in addition to providing insights into how institutions communicate online.

Back to Top

Home | Current

Issue | Archives | Editorial

Information | Search | Interact