Nathaniel Kohn

Assistant Professor

College of Journalism and Mass Communications

University

of Georgia

nkohn@arches.uga.edu

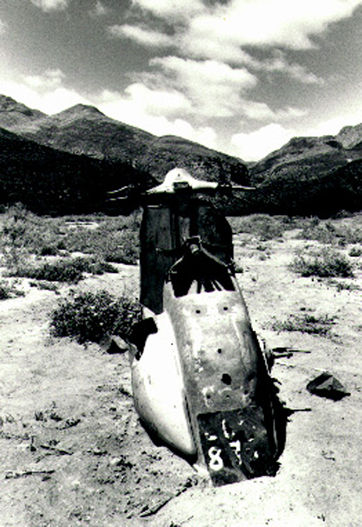

All photographs by Trix Render

![]()

"Are you writing this down?" asks Trix.

"Some of it," I say. "The occasional line or phrase. Some things to ponder3 over, perhaps."

I hear her lighting one of her small cigars, the badly rolled black Pockets that Dieter sends her from Munich. Trix on the other end of the telephone line, a thousand miles away, in New York City.

I envision her sitting on the love seat in front of the window, the large sheet of clear plastic still taped to the frame against the cold, distorting the gaseous lights outside. The large red curtains, so brilliant in the sun, now heavy and muted, blood black in the dead of night.

"Good," she says. "I want you to write me again. I want you to make me famous. God knows I'm never going to make it by myself."

"You are famous," I say. "In certain circles."

"Aach, yah," she says, in that South African accent of hers, betraying Afrikaner roots, summers on a farm in the Orange Free State, a born member of the white tribe.

"Aach, yah is right," I say.

"Fucking famous maybe," she says, "famous for fucking."

She laughs.

"Listen to me," she says. "Just listen to me."

I write down "fucking famous...famous for fucking" on a yellow legal pad next to the key board. Then I write "Orange Free State." With my right hand, I open a computer file.

Words on the screen:

| draft

Look at Us Now: Celebrity and the Third Space4 Homi Bhabha's Third Space5, Giorgio Agamben's Coming Community6, Trinh Minh-ha's Third Scenario -- we attempt to take these concepts, among others, and meld them into a working scenario of celebrity in postmodern times. For Bhabha, Trinh and Agamben the redemptive strategies/spaces of our times occur primarily in liminal spaces -- unstable spaces in between, on the threshold, spaces that encompass... |

"I know," she says. "Sometimes I amaze

myself."

"Do you want to see some pictures?" asks Trix.

I am in her apartment for the first time, a crooked place above a diner in Long Island City, one long subway stop from Grand Central, just across the East River, behind and under the large Pepsi sign that UN bureaucrats gaze at through bluegreen-tinted panes. Long Island City, a Italian Greek enclave seven minutes on the 7 train from the hurly burly, lost in the 1950s, languishing in a time warp of short decaying buildings and badly angled streets.

Trix's rooms seem to have no corners, Van Gogh rooms where round things always roll, never coming to rest.

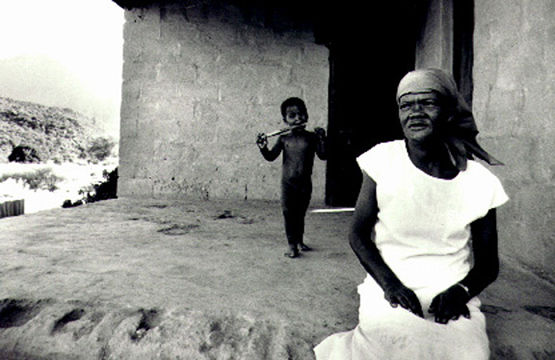

The first picture is black and white, the face of an extremely old black woman, taken in blinding sunlight, a thinning tangle of white hair bleeding into the white sky that surrounds her. Her eyes are gray and filled with spots, the irises indistinguishable from the whites, the pupils so small that I cannot locate them. Her skin is heavily lined, deep crevices that wind their way across her forehead and down her cheeks into her neck, empty rivers worn smooth, no doubt unexpectedly soft to the touch, not yet ready to crumble. An unbothered upside down fly, its wings limp and transparent, clings to her chin.

"I took that on my grandmother's farm in the karoo near Buffelsklip," says Trix. She sits on an orange crate across from me, leaning forward, her back straight and long. Her knees are touching mine.

"And the woman?"

"Aach," says Trix, "she's always been there, since I was a child. Everybody is related to her in some way. Great face, huh?"

"Nice photograph."

"I took it just before Christmas," she says. "Maybe next year I'll make Christmas cards out of it."

Trix places another one on top of the old woman.

"And this," she says, "is me."

And it is, completely naked, sitting on the same uncomfortable green metal garden bench where I now find myself perched. Her arms hang long and thin along her sides, her whole body thin, bones showing, sticking out, breasts small and high as if moved out of the way so as to reveal knobbed ribs above the sunken cavity of her stomach above almost fleshless hips and legs, starkly white in the light of a single flash, a motionless concentration camp body. And, instead of a face, a streak of shiny red hair, long and alive like a cracking whip, a taunting highlit blur moving too fast for the fastest shutter.

Trix laughs.

"Funny, huh?" she says.

"Nice," I say, "nicely done."

Trix, the tall thin South African model, always covered from head to toe in black or green, so beautiful as to be intimidating on the streets of New York, yet also so shy, always refusing to go to the pool because she doesn't like how she looks in a swimming costume. Trix, now naked before me.

She laughs again.

"I'm shocking you," she says.

"No...."

"I took it myself," she says, "with

the timer. Don't you just love it?"

"I did," she said. "It was a madhouse, hundreds of people, quite exciting. I knew there were a lot of South Africans in New York, but Jesus, it looked like New Year's Day at Camps Bay...."

"And who'd you vote for?"

"The ANC, of course," she says, pronouncing it as a word, anck, not spelling out the letters like they do on television.

"The anck?" I say, repeating. "You call them the anck?"

"Everybody does," she says. "Like the sound a pig makes."

"You're calling Nelson Mandela a pig?"

"Aach, man, no," she says. "It's just a sound, faster to say than A-N-C."

"Fewer syllables," I say.

"Fewer," she says. "Although I did vote for the Nationals in the Western Cape. They're sure to win there, not enough ancks in the Western Cape."

I write down, "ANC = anck... like ankle... or knee or foot... a pig sound..."

I page down on the computer screen:

| ...Agamben's "perfect exteriority," that transcend dialectics of recognition, spaces with new futures, different temporalities, histories, and terminologies, spaces that offer the hope of fresh political possibilities, that constantly interrogate the taken-for-granted categories of race, gender, class, et cetera... |

"Because he could see it coming?"

"That's right," says Trix. "Because he knew it would happen while he was in power, because he knew he would help it happen. 'On our watch' was how he put it. Like he was fucking Churchill or something. That was shortly after P.K.'s stroke. Or maybe shortly before. I can't remember."

"Pik Botha fucked Churchill?"

"Maybe," says Trix. "If not, he will in the movie version."

"Listen," I say, "to what Rey Chow says. I'm putting her in this paper I'm working on...."

"You're going to read to me again?"

"Consider yourself one of the privileged few," I say. "So, Rey Chow says, 'It is only through thinking of the other as sharing our time and speaking to us at the moment of writing that we can find an alternative to allochronism. --' Allochronism is a nation-centered theory of culture. '--The position of the feminized, ethnicized spectator, as image as well as gaze, object of ethnography as well as subject in cultural transformations, is a position for which coevalness is inevitable.7'"

"I'll buy into that," says Trix. "We can never have too much coevalness."

"I thought you liked it when I read to you," I say.

"I do," says Trix. "Most of all when you are reading me something you wrote about me, about how you're going to make me famous."

"Indulge me," I say.

"Indulge me," she says. "Here's something you can write down and read back to me next month, before you send it to The New Yorker or give it to some professor."

"You've had an adventure," I say. "Why'd you wait so long to tell me?"

"Teasing you," she says. "Waiting for you to ask. Remember the diner, the one downstairs?"

"Nate!"

It is Trix's voice. She sits alone in a red plastic booth. I slide in across from her.

"You found it okay?" says Trix.

"Easy," I say. "You give good directions."

"Pete," she says to one of the counter men, "bring my friend a glass of orange juice."

Pete nods and says, "Sure, Trix."

"It's good here," she says. "Greeks always squeeze good orange juice."

She already has a glass full in front of her on the formica table top, a yellow-tinted plastic glass, the kind of plastic you can taste. She reaches up into her piled high auburn hair and pulls out a small long handled silver spoon. It looks Victorian, delicate. With it she shovels a large amount of blue-green algae from a dark brown bottle into the juice and stirs. Instantly, as if through the magic of alchemy, the orange liquid turns black-green. She lifts the glass to her lips and drinks it down, chugging it, as if it were muddied green beer in Chicago on St. Patrick's Day. She puts the glass down and smiles at me. Her teeth are green.

"Your teeth are green," I say.

"Like my eyes," she says.

And she laughs.

"Like your soul," I say.

"Like Africa."

"Like money."

"Like my hard hard petrifying heart," she says, and she laughs again.

Without a word, Pete puts a glass of orange juice in front of me, the plastic touching the formica with a certain hollow indifference.

"So," she says, "this is my diner. Isn't

it everything I told you it was? Don't you just love it?"

| Bhabha's Third Space is a possibility opened up only to those living in the colonized position; that is, the Third Space is a way in which the subordinate undoes and unsettles the dialectic of the colonizer. Agamben's Coming Community is born in oscillation, moving between communion and disaggregation, a community completely without presuppositions. Trinh Minh-ha's assault on binarisms finds the challenge in the hyphen itself, "the realm in-between, where predetermined rules cannot fully apply8." |

I write "diner" on the pad, followed by "liminal space... between here and here...." I write "Trix" with lots of Xs overlapping.

"When was it?" says Trix. "Last Thursday night I think. I was in there late with Janine, having some coffee. Around midnight these five guys walked in. Four of them were real heavy dudes, lots of black leather covered in lightning bolts and skulls and things. Biker types. The real thing, not drugstore. Short short hair, earrings, big boots, brass knuckles, big guys, young, tough. The fifth guy was short and old, bags under his eyes, carrying a beat up old briefcase. They all crammed into a booth. I mean, guys like this don't come into my diner."

"Sort of out of place," I say. "Between here and here, out of gas, out of luck."

"No, not like that," says Trix. "They were having a business meeting of some kind. They were writing on napkins. One of the guys was, well, you know, kind of cute, tall and cute. I pointed him out to Janine and she agreed. Once he caught me staring at him and I said, 'Nice jacket,' something dumb like that. He smiled, but didn't say anything. Janine kept nudging me, telling me to go over and introduce myself, say something to him, but I didn't. I mean, I don't do stuff like that. You know that, I don't."

"I know," I say. "Guys come up to you."

"All the time, the fuckers," says Trix. "Anyhow, after a while Janine and I left and went up to my place -- it's right upstairs, you know...."

"I've been there. I know."

"So, it was about half an hour later and Janine and I were drinking some wine and she kept telling me that I should have said something to him, given him my phone number. She was kind of goading me, but I liked it, I didn't care. After a while -- and remember I've never ever done anything like this before -- after a while I picked up the phone and called the diner. Pete answered and I asked him if those guys were still there and he said yeah they were. I described the cute one to him and Pete said did I want to talk to him and I said yes I did, so he called him over to the phone. He picked it up and -- now this was really embarrassing, but what can I say? -- he said hello in some foreign language and I said, 'I'm sorry I don't speak Italian,' and he said, in English, 'it's not Italian, it's Portuguese.' I wanted to say it's all Greek to me, but I didn't, didn't want to be too flip, I just told him that I was the girl who liked his jacket and I said I thought he was cute and if he wanted he could give me a call sometime...."

"So you gave him your number? This guy you've never met? In New York? You did that?"

"I did," says Trix. "Like Mae West would have done."

"Jesus, Trix," I say.

"Jesus," says Trix, "is right."

I write on the pad, "Holly Golightly...New York in the '50s, Truman Capote" then I draw a big X through it, like Derrida would do. I open the computer clipboard and find:

| Trinh on the hyphen: "It is having to confront and defy hegemonic values on an everyday basis...that one understands both the predicament and potency of the hyphen...a transient and constant state: one is born over and over again as hyphen rather than as fixed entity, thereby refusing to settle down in one (tubicolous) world or another9." |

"So," I say, "then what happened?"

"Nothing. He didn't say anything and I hung up. About an hour later the doorbell rang and he was there."

"And you let him in."

"I did. He came up and had some wine with Janine and me. Turned out he's Brazilian, kind of shy, quiet, in this band with the other guys in the diner. They rehearse in an old warehouse over by the river. The old guy's their manager. He's English, used to manage the Sex Pistols or something."

"The Sex Pistols?" I say. "Couldn't he have said something more au currant, like Nirvana maybe? He actually said the Sex Pistols?"

"It's New York," says Trix. "And he said the Sex Pistols. How was I to know what was true? How do I know anything's true? He could have been an alien. He could have been an axe murderer or something. He could be anything. He could even, possibly, be something close to what he says he is. I mean, I could be an axe murderess, too. How would he know? How would anybody know? Until I hauled out the axe or something."

"You could be an axe murderess," I say. "I know some people who think you are."

"Stop it," says Trix. "I don't even own an axe. A chain saw, yes, but not an axe. Be kind, now, or I'll stop."

"I'm always kind," I say. "You know that. You know me."

"I'm telling you this because you asked."

"I did?"

"You always do," she says. "Sometimes not outright, but you always ask. Otherwise, why would I bother?"

"Because you think I'll write it all down and make you famous?"

"Because you listen," she says. "Because I love telling you things. Because my life's like a subway stop."

"Like a subway stop?"

"So many people passing through," she says. "I have to tell somebody just to keep track."

"And you tell me."

"I can't stop," she says. "Doing stuff and telling you about it."

"You the addict," I say. "Me the drug."

"I know," she says. "There's a party in my head and you're always invited, no cover charge."

"Lucky me," I say. "So, tell me more. Please."

"Well," she says, "after a while Janine left and we sat there, staring at each other and I thought, my God, what a handsome devil, shy, with a nervous smile, his hand shaking. At times, he was shaking all over, maybe more scared than I was. I mean, he was like a little boy. So, we smoked a joint."

I page down on the computer to the next screen:

| We see these philosophers (although their languages differ) privileging performativity as the major consciousness in/of the alternative spaces they seek to reveal -- the inbetweenness and thresholdness of the flow of human life in culture is enacted through performativity. They stress the many modes/levels of being/experience that are performed: people, living and moving in culture, metaphorically seeing and trying to read themselves and others in signifying actions, strategies, costumes, identities. In his descriptions of these spaces, Bhabha notes their ambiguity and temporary natures, but nevertheless points to the empowerment that comes from residing in and about these communities, from performing in the Third Space. |

"He's a rock star, then, this guy?" I say. "Does he have a name? Have you learned it by this time?"

"Yes," says Trix, "I have. It's Supla. His name is Supla...."

"Can you spell that?"

"S-U-P-L-A."

I write it down.

"That's a Brazilian name?" I say.

"How would I know?" says Trix. "It's his name. I know that for sure; I saw it sewn into his underpants."

She laughs. I hear her lighting another cigar, no doubt with the old Zippo lighter she keeps in a Gucci shoe box next to her bed.

"You know what Toni Morrison says about names, what Beloved, one of her women characters, says?"

"No."

"She says, "'I want you to touch me on my inside part and call me my name.' It's about a desire for identity, a desperate cry10."

"It's sad," says Trix. "I know what she means. I want that too, sometimes."

"Even from a rock star?" I say.

"Fuck you," says Trix.

"I love it when you say that," I say. "When I can make you say that."

"And yes, even from a rock star," says Trix. "He is a rock star, you know. At least in Brazil. He also plays polo and acoustic guitar and he's a boxer, too. His father is a politician of some kind, a state senator or something, and his mother is a psychologist. He says she is the Dr. Ruth of Brazil."

I write down "Dr. Ruth of Brazil...underpants" and I underline "pants" and write next to it, "not underwear..." And then I write "See Homi Bhabha on Toni Morrison and Nadine Gordimer....11"

So," I say. "How old is Supla?"

"Two years younger than me," says Trix. "He's 28, a nice age for a boy."

"And his astrological sign?"

"Aach, man!" says Trix.

"Okay," I say. "Okay...."

"So," says Trix, "I told Supla that I never did this on the first joint...."

"This?"

"And that. You know, fuck. It was kind of a joke, because we hadn't done it yet and it didn't look like we would. He laughed. We sat there talking for another hour or so, it was now like four in the morning or something and we were both so so tired we had no idea what we were saying. So I suggested that we take a bath."

"A bath?" I say.

"Yes."

"In your tub?"

"In my tub."

"I've been saving it for last," says Trix. We are in her kitchen. There is no stove, no refrigerator, no hot plate. Just an old toaster oven covered with dust and a rust colored sink with a broken pizza box in it.

"This way..."

We walk halfway down an uneven windowless corridor. On one wall there is a heavy green curtain. She pulls it back.

"And this," she says, "is my bathroom."

It is tiny, not even a room, more like a shallow cave hacked out of the wall. There is a toilet and a large sink, that is all. I look at the sink. It is a shiny silver stainless steel restaurant sink, three feet square, sitting a few inches off the concrete floor on bricks.

"That's your bathtub?"

"Yes," says Trix. "Isn't it magnificent?"

"It's a sink," I say.

"I know," she says. "Well, let's say it was a sink. Now it's a bathtub. My bathtub. Where I live."

On a small shelf to the side of the sink and on the floor around it are dozens of half-melted green candles and green bottles with charred incense sticks in them. On the back of the toilet are open perfume bottles, most filled with greenish liquid, and in a box between the toilet and the sink are several bottles of photo-finishing chemicals.

"I put it in myself," says Trix. "I hammered out the door frame so I could get it in and then I poured that concrete slab and I hung the curtain so I can also use it as a darkroom. I did all the plumbing myself, too."

"Isn't it a little cramped?" I say. "I mean, you must be six feet tall...."

"Five ten and a half," she says. "And no, it's not cramped, it's perfect. I'm a lot more flexible than you'd think. Here, look."

And she climbs into the tub and sits there, her knees up either side of her face, smiling, content.

"I can even do this," she says and she pulls one leg up behind her head, effortlessly, naturally.

"I spend hours in here," she says. "It's my favorite place in the whole world."

"A three foot by three foot by three foot stainless steel box?"

"Exactly," says Trix. "I bring my phone and my bottle of champagne and I'm in heaven."

She puts her leg down, hugs her knees and laughs.

"I know you think I'm crazy," she says.

"Well..." I say.

"Come on," she says, "take my picture. Memorialize me and my bathtub."

I pull my Olympus Stylus from my pocket

and snap off several frames.

"Must have been a tight fit," I say.

"It was," says Trix. "He's like six-four or something. I've never known a guy that tall. It's nice, nice having someone tall, someone who is really taller than me. It's a cliche, I know, but it's nice, bending my neck that way."

"He's as flexible as you, then?"

"And gorgeous, too," she says. "All rippling muscle and smooth smooth skin. It was a perfect fit in my tub, two peas in a pod."

"One South African, one Brazilian."

"Exactly," says Trix.

"One a famous photographer, the other a famous rock star, meeting by chance in Long Island City," I say. "A place in between."

"Exactly exactly," says Trix. "Exactly."

On the computer screen:

| In our essay, we take the concept of celebrity (and its pursuit) in postmodernity -- celebrity generally referring to fame, achieved recognition and other qualities associated with movie stars, sport heroes, Hollywood, the tabloids, being on/in television, in the movies, in the public eye, etc. -- and explore such celebrity as one working example of a Third Space or Coming Community. |

"I know," she says. "Did I tell you that the name of his band is Psycho 69? It's heavy, heavy metal, high energy, and Supla, gentle Supla, writes all the songs."

"No, you didn't tell me," I say. "So, it's not world beat."

"God, no," says Trix.

"You won't find Willie Nelson re-recording Supla songs in about ten years, then?"

"I don't think so," says Trix. "For that kind of thing, for heavy metal, it's good. I mean, I wouldn't buy it, but I don't mind listening to it."

"And there's nothing Brazilian about it?"

"Nothing," she says. "Except him. He's Brazilian. What comes out of his mouth is Ozzy Osbourne, a better Ozzy Osbourne than Ozzy Osbourne. Anyhow, do you want to hear the rest of what happened or not?"

"I do," I say.

"Well," says Trix, "we still hadn't actually done it. I mean, we'd played around and stuff, but we hadn't actually fucked. You know how you are when you get so tired your eyes start swimming and things that aren't supposed move start moving and won't stop? Well, we were that tired. Somehow, we got from the tub to the bed and fell fast asleep. I woke up about eight, he was still sleeping, still there, and I ran into Beto's room--"

"Who?" I say.

"Beto," says Trix, "my new roommate, the Venezuelan gay guy. You didn't meet him?"

"No," I say.

"He's sweet," says Trix. "I woke him up and said that I had this beautiful beautiful man in my bed and I didn't know what to do. And he said, 'Trix, Trix, go for it! My God, Trix, don't think about it, go for it!' And he gave me some really expensive condoms. So, I went for it."

Trix giggles.

I write down: "Beto...Venezuela...condoms...."

"And?" I say.

"And," she says, "it was really great. Jesus, it was great. He's got this incredible body, thin and strong with lots of muscle, really well defined, soft and hard at the same time. It was fantastic. He didn't leave till close to noon. I just couldn't get enough of him. His stomach is like a riddle of muscles that I can ride like a wave."

"What did you say?"

She laughs.

"I said," she says, "his stomach is like a riddle of muscles I can ride like a wave."

I write that down, word for word.

"Beto got a look at him and he said to me, 'My God, Trix, beautiful face, big legs, big ass, perfect, congratulations!'"

I am writing fast now.

"You do a wonderful Spanish accent," I say.

"I know," says Trix, "I've been practicing."

"And Supla," I say, "how'd he like it? How's he like you, do you think?"

"I don't know," says Trix. "What's more important is how much I liked it. He's like a combination of a wild cat and a pussy cat, a wild dog and a tame dog. I could show him what I liked and he'd do it like I wanted, only better. It was fantastic."

"So you sort of used him," I say. "Exploited him."

"I'm a cultivator, not an exploiter," says Trix. "I'm a gardener."

I write down "cultivator, not exploiter, gardener...chauncey gardener...secret garden of delights...rain forest...the garden route, joburg-cape town...."

"That's nice," I say.

And I write, "cultivate=culturate...enculturate...."

"And he's so big," she says, dragging on a cigar, "what's the phrase?...so well endowed."

"He is?"

"Gigantic," she says. "Beto says all Brazilians are big. It's a national characteristic. And Beto should know."

"And it makes a difference?"

"Yeah," she says, "it does. I know people say it doesn't, I used to think it didn't, but yeah, it does, it makes a big difference."

"And it's an essential Brazilian characteristic."

"It could grow to become essential, yes," says Trix. "I could become addicted to big dicks."

I write down: "essentialist...Brazil...well endowed...."

"Just listen to me," says Trix. "Listen to how I am talking."

"I know," I say. "And you've never done this before."

"I haven't," she says. "It's the first time. Honest to God. I have never picked up anybody before, ever. Never slept with anyone on the first date, ever. Never."

She laughs.

"Funny, huh?" she says. "With a Brazilian. With a rock star."

"Strange."

"You know," she says. "I think he's used to having groupies, I mean he must, being a singer and all. So, I was thinking about that, and I said to him at one point, 'I'm not your groupie, I'm no one's groupie, I'm my own groupie.'"

"And?" I say.

"He laughed," she said. "He's very funny, you know. Very sweet and innocent in his own way, with that kind of easy Latin self-confidence, making a joke of it. Non-threatening when he wants to be, in spite of all the leather and shit."

I page down on the computer screen.

| Celebrity appears to meet some of the criteria of Bhabha's Third Space: in celebrity, contemporary discourses are mimicked, parodied, erased; in celebrity, where performativity is truly privileged, hegemony can be contested; in celebrity, we may find a kind of "perfect exteriority." Certainly, (what passes for) the masses recognize celebrity as a Third Space, one of the few redeeming strategic positions open to them in a postmodern world. That is why, in part, everyone everywhere seems to be questing after the salvation promised by Warhol -- the infamous 15 minutes of fame. |

"And he just left?" I say.

"He had a meeting or something, he had some place to go," she says. "And I had work to do. He said he'd call or maybe stop by. A great story, huh?"

"Great."

"You'll write it, then?" she says.

"You should write it," I say.

"Aach," says Trix, "how can I? I'm living it."

With the down arrow key, I bring up the next paragraph:

| We discuss within our work -- which itself is constructed as performative -- whether celebrity is institutionalized liminality, whether celebrity can be theoretically constructed/deconstructed as a Third Space. Finally, we look at how we celebrate ourselves, as we explore the space(s) in which we find ourselves to see if we indeed are crying for attention from a place of (in)difference, somewhere in between. |

Trix, her face white and her hair approaching the color of African mahogany in the coldly angled winter sunlight, is dressed in high fashion black -- black boots with raised heels and soles, a long fitted black skirt severely slit to reveal black tights, a jacket too thin for cold colored a dark dark green, like the black-green of the lowest leaf in the thickest corner of a Brazilian rain forest.

She stoops to pick up a twisted piece of metal about the size of a crowbar, a tangle of rusting steel cut in no particular shape, a seeming remnant from a disgruntled CNC machine, probably fallen from the bed of a passing junk truck, jarred loose by an angry pothole.

"I like this," she says. "What do you think?"

"It looks kind of heavy," I say. "Kind of vicious."

"I can use it in my welding class," she says. "It can be a part of what I'm making, my project, my post-atomic rose."

"Welding class?"

"I'm making this gnarly, twisted rose," she says. "It's as tall as I am, with a five foot stem. Mostly its ragged gun-metal gray, but with streaks of silver in it, really rough. It's going to be a lovely piece, weighs a ton."

"Made from scrap metal you found on the street?"

"Yes," she says. "On the streets of Long Island City and in the scrap heaps behind the abandoned factories over there, toward the river."

"A scavenger."

"Pepe gave me a large metal key and a small metal heart," she says. "They're a part of it, too. I made thorns out of them."

Trix laughs.

"Pepe?"

"Pepe's Spanish or Mexican or something," she says. "Just a friend, an Upper West Side boy from south of the border, teaches the tango or something. Sweet Pepe, like a sweet red bell pepper, my sweet Pepe."

"Jesus, Trix."

"I know," she says, "but I can't help it."

We pass a garage with an open door. Inside are half a dozen yellow cabs in various stages of undress, dirty men exploring their gritty bowels with gleaming socket wrenches. A knot of men stumbles out into the street behind us and we turn to look. Cab drivers, mostly Indian, some Sikhs in turbans who are smoking brown cigarettes. They look after us for a second, then huddle around a lamp post and speak words to each other in a language I can neither understand nor identify.

Trix slips the piece of twisted metal into her large black bag.

"Stupid fuckers," she says. "The taxi companies all have garages along here because it's so close to town. The drivers are always hanging out, leering, like they were back in Bangladesh or someplace. You'd think they never saw a white woman before, never saw a fucking movie."

We round a corner and walk down a broad street toward the river, past the loading docks for the Pepsi bottling plant, the one with the large sign that so dominates the view from the United Nations. A few women, mostly young, black, and giggling loudly, drift away from the large doors and make their way up toward Vernon Avenue. Their voices hush as they pass us.

At the water's edge, I absorb the view. Manhattan's classic skyline shimmers before me, a picture postcard.

"Look at that," I say.

I point directly across the river to a street that runs toward us, an open space between the tall buildings, a space that bisects the island, a space of white sky for as far as the eye can see, starting at ground-level and extending heavenward, separating the tall buildings, cutting their jagged flow in half.

"Strange," says Trix. "I never noticed that before."

"I wonder what street it could be," I say. "Maybe Forty-Second Street."

"Maybe," says Trix, looking down the street, her gaze filling the space. "Somebody cut Manhattan in half and left a little space in between. It's lovely."

"Forty-Second Street," I say. "Busby Berkeley's street."

"I'm going to put my post-atomic rose on wheels," says Trix, "so I can roll it around my apartment. I want it to feel at home all over my place, to be wherever I am, to go wherever it wants to go. The rose part is going to be a candle holder."

"A six foot tall candle holder?"

"For a big fat green candle," says Trix. "One that will shine a little light on me."

| Until this century, mass populations in human communities had little opportunity for expressing imaginative impulses in large mediatized spaces such as those that now abound in television, film, sport arenas, amphitheaters. In pre and early modernity, fantasies for common folk were restricted to rituals, song, dance, story-telling, fairs, plastic arts -- all localized narratives. Only nobility, gentry, the elite, had the resources to flesh out creations in the shape of things like pageants, theater, pamphlets, distinctive dwellings, athletic pursuits, gardens and other fanciful structures. However problematic it is to construct events out of time periods, or even to label a time period as a construct, we must still notice, within the artificial categorization of post/modernity, how self-expression, playfulness, and celebrity are enabled on a large and accessible scale for most people in the communities of both the "developed" and "undeveloped" worlds. |

"Nothing ever ends," says Trix. "I end things sometimes, but they never really end. If I'm lucky, things mostly just go away."

"You saw him again, then."

"He came by and then we went into town," she says. "The night before last. After a late dinner, we went to his place. It was fun. I bought a vibrator along the way, especially for the occasion."

"For size comparison?" I say. "One of the dildo kind?"

"You're bad," says Trix. "You really are."

"I am?"

"You just say things to get me to say things," she says. "You're a bad fucker."

And she laughs.

"But yes," she says, "I did do a little comparing. He won, hands down."

"He did?"

"Of course," says Trix. "What do you think?"

I write down: "vibrator... welding... post-atomic rose/big green candle... space between skyscrapers...."

"Where does he live?"

"In town," says Trix, "on Avenue B between twelfth and thirteenth, a pretty dodgy part of town. He has a tiny place, a little apartment. With a cow's foot hanging outside his door."

"A what?"

"A cow's foot," says Trix. "A real cow's foot above the door and off to the left."

"To ward off evil spirits, I guess."

"I don't know," says Trix. "Probably. I didn't bother to ask it's function. It was clean, though. It didn't smell. A beautiful hoof, with hair on it."

"A cow's foot," I say. "He probably brought it all the way from Brazil."

"He showed me lots of photos and newspaper clippings from Brazil," says Trix. "Pictures of him performing with Billy Idol, CD covers, fan club pictures, magazine layouts showing him performing at rock concerts, stuff like that. So, he must be pretty famous there."

"Yet he's here," I say, "on Avenue B, trying to look like a heavy metal rocker."

I write: "See Bhabha on mimicry..." I leaf through a book and jot down: "'...to be effective, mimicry must continually produce its slippage, its excess, its difference12."

I leaf a few pages further, skimming: "...under the cover of camouflage, mimicry, like the fetish, is a part-object that radically revalues normative knowledges of the priority of race, writing history. For the fetish mimes the forms of authority at the point at which it deauthorizes them. Similarly, mimicry rearticulates presence in terms of its ‘otherness,’ that which it disavows."13

"His place is pretty funky," Trix is saying. "The window is covered by this huge American flag and there are big leather whips draped over chairs and things, but the walls themselves are bare, nothing on them. I told him I liked the bare walls, and he said he did, too, but that they'd be even better when he put up some pictures. I asked him what kind of pictures and he said, 'Babes on Bikes.' Babes on Bikes, can you imagine? He said it like it was the most natural thing, like everybody has posters like that on their walls. For the first time I thought, let me out of here."

"Babes on bikes?"

"I know," says Trix. "Believe me, I know. But, then, to be fair, under his pillow on his neatly made bed were a pair of perfectly folded black silk pajamas. So tidy it made me melt. And you know what he had on his boxer shorts?"

"No."

"Jumbo the elephant," says Trix. "Lots of little playful Jumbos. He has another pair with little green dinosaurs on them that glow in the dark. His mother gave them to him. His mother still gives him underpants. Dr. Ruth gives him underpants. How can you not like somebody like that? Somebody who wears baby dinosaurs under his studded leather?"

"Sounds like he might be a little confused," I say. "Like he skipped a couple of rungs on the cultural evolutionary ladder. That happens, when people move too quickly from there to here."

"He might make it, you know," says Trix. "His music is okay, and he's so fucking good looking, tall dark and handsome."

"'Touched by this swarthy tint spreading like an oil stain over the world,'"14 I say.

"What?" says Trix.

"Something I'm reading," I say. "A quotation."

I page down on the computer, bringing up more of the rough draft.

| That almost anyone

has a chance to be on television, to gain a part in the movies, to participate

in a talent show, to be spotlighted as an athlete, is quite specific to

the present age. That this is so tells us a great deal about the present

age as, to use Grossberg's phrase, "a place of possible events; a voyage,

a fantasy of future possibilities."15 One

of the things Grossberg urges us to notice is how popular practices construct

these places, how place constitutes what can happen. Within the third space

celebrity, we can apply Grossberg's idea and note that the popular practices

of celebrity are practices that do not just construct this place (1990s

earth): they actually become this place. The place of possible events --

the voyage, the fantasy, the untranslatable -- thrives within celebrity.

The practice and the geo-historical places of celebrity...

...become world spaces, spaces that empower, spaces that restrict. The space of celebrity itself has become the signifier, the negative, the excess, the redemptive and more. |

"Of Supla?"

"Of Supla," says Trix.

"What happened?"

"Aaach," says Trix, "nothing, really."

"Come on," I say.

"Well," says Trix, "we were walking to his place and it was really late and really cold out. And we were walking fast. You know how fast I can walk, but he was walking faster, three or four paces ahead of me. He looked back and told me to hurry up. That's all. Just hurry up. And I said, 'Fuck you, I'm not a dog. Fuck you.' That's all. I just didn't like that, his tone of voice."

"When was this?"

"On the way to his apartment the other night."

"Just before the Babes on Bikes?"

"Yes," says Trix. "I know what you're thinking, but I decided I wouldn't let it spoil my evening. I mean, it wasn't really that big of a deal. I said fuck you to him a lot, just like I say it to you, to everybody. And we really had a great time that night. It was a lot of fun. But I kept thinking about it, his talking to me like I was a dog or something, a kaffir or something. I knew it'd never lead anywhere. He was also rude to the cab driver on the way into town. And he's a mean tipper. I mean, the little things kind of add up, when you think about them. So, I called him yesterday and I said I was sorry, but I didn't want any more of this, that I'd had a really good time and that's how I wanted to remember it."

"And?"

"And he said okay," says Trix. "He's really into his music. He'll handle it okay."

"And you?"

"Aach," says Trix, "you know me."

"So, you ended it."

"As best I could," says Trix. "With the memory still pleasant and sweet. Such a sweet little Brazilian boy."

She takes a deep drag on a cigarette, the inhalation loud and long. I hear a distant siren and the purr of a cat.

"So," she says, "what do you think I'm doing now?"

"Now? At three a.m.?" I say. "Besides talking to me?"

"Besides talking to you."

"I don't know."

"Guess," she says.

"Well," I say, "I'd say you are sitting on your love seat next to the red curtain and staring out your window at the subway stop, idly wondering if he might walk up the steps into the desolate green glare, wondering if you might discover wonder itself in his stare as he looks up toward the blood red light in your Long Island City window, wondering, perhaps, if he might serenade you in Portuguese, a soulful fado, maybe, a bittersweet lament."

I pull up the final paragraph of the rough draft:

| The space of celebrity is not like the spaces that Spivak16 and others talk of; it is not opened, as Spivak asserts in her discussion of postcoloniality, by the colonizer, or by excess or negation. Further, the celebrity space is more than a liminal border space, more than a privileged moment. We want to work with the idea that celebrity spaces are what Grossberg would call the trope beyond that of Homi Bhabha, more closely allied to Rey Chow's ideas of spaces as those of exteriority, or possibility as event.17 For us, celebrity is a space that is "an experience that exhausts the resources of language,"18 that begins to get outside the construction of difference; a space that begins to play with and discard particular historical relations of power. The space of celebrity is culture itself, and this culture is, as Grossberg argues, "a way of becoming." |

trix

>. 2. geometric line, point, surface <genera

trix

>...'"

"Is that about right?" I say.

"Fuck you," says Trix. And then she laughs and says, "I know you love it when I say that."

"I do," I say. "Among other things, I guess it helps me feel a part of it all."

"And you still long for that?"

"Still and always," I say. "Just like you."

"Well, fuck."

"Fuck," I say, "is right."

Endnotes

1 Trinh Minh-ha. (1991). The moon waxes red. New York and London: Routledge. (p. 23)

2 Bhabha, Homi. (1994). The locations of culture. New York and London: Routledge. (p. 12).

3 In part, I am encouraged in my method -- my pondering -- by Walter Benjamin. See Susan Buck-Morss, The Dialectics of Seeing: Walter Benjamin and the Aracades Project, pp 240-241, on Benjamin’s ponderer/allegoricist: "The case of the ponderer is that of the man who has already had the resolutions to great problems, but has forgotten them. And now he ponders, not so much about the thing as about his past meditations over it... The memory of the ponderer holds sway over the disordered mass of dead knowledge. Human knowledge is piecework to it in a particularly pregnant sense: namely as the heaping up of arbitrarily cut up pieces, out of which one puts together a puzzle. [...] The allegoricist reaches now here, now there, into the chaotic depths that his knowledge places at his disposal, grabs an item out, holds it next to another, and sees whether they fit: that meaning to this image, or this image to that meaning. The result never lets itself be predicted; for there is no natural mediation between the two."

4 See Nate Kohn and Synthia S. Slowikowski (1994), "Look at us now: celebrity and the third space," unpublished paper presented at the Society for the Study of Symbolic Interaction Annual Meetings session on Postmodernism and Cultural Studies II, Los Angeles.

5 See Bhabha, Homi (1994). The location of culture. New York and London: Routledge.

6 See Agamben, Giorgio (1991). Theory out of bounds: the coming community. (M. Hardt, trans.). Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

7 Chow, Rey. (1991). Woman and chinese modernity: the politics of reading between west and east. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press. (p. 33).

15 Grossberg, Lawrence. Class notes from lecture May 3, 1994, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

16 See Spivak, Gayatri (1988). Can the subaltern speak? In Cary Nelson and Lawrence Grossberg (eds), Marxism and the interpretation of culture (pp. 271-313). Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

17 See Chow, Rey (1993). Writing Diapora: tactics of intervention in contemporary cultural studies. Bloomington and Indianapolis: University of Indiana Press.

18 Grossberg, Lawrence. Class notes from lecture May 3, 1994, University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign.

![]()

Selected Bibliography

Abbas, A. (1990). Disappearance and fascination: The Baudrillardian obscenario. In A. Abbas (Ed.), The provocation of Jean Baudrillard (pp. 68-93). Hong Kong: Twighlight.

Agamben, G. (1991). Theory out of bounds: The coming community. (M. Hardt, trans.). Minneapolis: The University of Minnesota Press.

Arendt, H. (1968). Introduction. Pp. 1-59 in Illuminations by Walter Benjamin. New York: Schocken Books.

Baudelaire, Charles (1964). The painter of modern life and other essays. (Jonathan Wayne, ed. and trans.). London.

Baudrillard, J. (1983). Simulations. New York: Semiotext(e).

Baudrillard, J. (1989). The anorexic ruins. (D. Antal, trans.). In D. Kampfer & C. Wulf (Eds.), Looking back on the end of the world. New York: Semiotext(e).

Baudrillard, Jean. Selected writings, edited and introduced by Mark Poster. Stanford University Press. 1988.

Benjamin, W. (1968). Illuminations. (Hannah Arendt, ed.) New York: Schocken Books.

Best, S. and D. Kellner (1991). Postmodern theory. New York: The Guilford Press.

Bhabha, Homi K. (1994). The location of culture. New York and London: Routledge.

Buck-Morss, S. (1989). The dialectics of seeing. Cambridge and London: MIT Press.

Carver, R. (1989). Fires. New York: Vintage Contemporaries.

Carver, R. (1989). What we talk about when we talk about love. New York: Vintage Contemporaries.

Chang, H. (1993). Postmodern communities: the politics of oscillation. Postmodern Culture, 4, paras 1-54.

Chatterjee, P. (1986). Nationalist thought and the colonial world. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Chow, R. (1991). Woman and chinese modernity: the politics of reading between west and east. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Chow, R. (1993). Writing diaspora. Bloomington: University of Indiana Press.

Clifford, J. (1992). Traveling Cultures. In L. Grossberg, C. Nelson, & P. Treichler (Eds.), Cultural Studies (pp. 96-116). New York and London: Routledge.

Clough, P.T. (1992). The end(s) of ethnography. London: Sage.

Clough, P.T. (1994). Feminist Thought. Oxford UK and Cambridge USA: Blackwell

de Certeau, M. (1984). The practice of everyday life. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Deleuze, G. (1985). Mediators. In J. Cray & S. Kwinter (eds.), Zone 6: Incorporations (pp. 268-280). New York: Urzone.

Denzin, N. K. (1991). Images of postmodern society: Social theory and contemporary cinema. London: Sage Publications.

Denzin, N. K. (1992). Symbolic interactionism

and cultural studies: the politics of interpretation. Cambridge MA

and Oxford: Blackwell.

Denzin, N. K. (in press, 1994). The lessons James Joyce teaches us. Qualitative Studies in Education.

Derrida, J. (1976). Of grammatology. (G. Spivak, trans.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Eco, U. (1973). Travels in hyperreality. San Diego: Harcourt Brace Jovanovich.

Foucault, M. (1978). The history of sexuality: an introduction, volume 1. New York: Random House.

Foucault, M. (1984). The Foucault Reader. (Paul Rabinow, ed.) New York: Pantheon Books.

Gamson, J. (1994). Claims to fame: celebrity in contemporary America. Berkeley: University of California Press.

Grossberg, L. (1992). We gotta get out of this place. New York and London: Routledge.

hooks, b. (1990). Yearning: race, gender and cultural politics. Boston: South End Press.

James, C. (1993). Fame in the 20th century. London: BBC Books.

Katz, E. (1980). Media Events: The Sense of Occasion, Studies of Visual Communications. Fall, 1980.

Krieger, S. (1991). Social science and the self. New Brunswick, New Jersey: Rutgers University Press.

Kroker, A., Kroker, M., & Cook, D. (1989). Panic Encyclopedia: The definitive guide to the postmodern scene. New York: St. Martin's Press.

Lyotard, J-F. (1984). The postmodern condition: a report on knowledge. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

Margolis, S. (1977). Fame. San Francisco: San Francisco Book Company.

McCannell, D. (1992). Empty meeting grounds. New York and London: Routledge.

Nancy, J-L. (1993). The birth to presence. Stanford.

Olalquiaga, C. (1992). Megalopolis. Minneapolis and Oxford: University of Minnesota Press.

Rosaldo, R. (1989). Culture and truth. Boston: Beacon Press.

Schechner, R. (1985). Between theater & anthropology. Philadelphia: University of Pennsylvania Press.

Schickel, R. (1985). Intimate strangers: the culture of celebrity. New York: Doubleday & Company.

Sedgwick, Eve Kosofsky. (1992). Epidemics of the will. Incorporations (Eds. J. Crary & S. Kwinter). (pp. 582-595). New York: Urzone.

Stallybrass, P. and A. White. (1986). The politics and poetics of transgression. Ithaca: Cornel University Press.

Stewart, S. (1984). On longing: narratives of the miniature, the gigantic, the souvenir, the collection. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Trinh, Minh-ha. (1991). When the moon waxes red. New York and London: Routledge.

Trinh, Minh-ha (1989). Woman, Native, Other. Bloomington, Indiana: University of Indiana Press.

Vattimo, G. (1992). The transparent society. (David Webb, trans.). Baltimore and London: Johns Hopkins University Press.

Virilio, P. (1989). War and cinema. (Patrick Camiller, trans.). London and New York: Verso.

Virilio, P. (1991). The aesthetics of disappearance. (Philip Beitchman, trans.). New York: Semiotext(e).

Virilio, P. (1991) The lost dimension. (Daniel Moshenberg, trans.). New York: Semiotext(e).

Weinstein, D. and M. A. Weinstein. (1991). "Georg Simmel: Sociological Flaneur Bricoleur." Theory, Culture & Society, 8, 151-168.

Young, R. (1990). White mythologies: writing history and the west. New York and London: Routledge.

![]()